According to the ADR, a staggering 158 MLAs (66%) have declared criminal cases against themselves. More alarmingly, 119 MLAs (49%) face serious criminal charges, including murder, attempted murder, and crimes against women.

It is a story of India’s fraying democratic fabric. A new report by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) and Bihar Election Watch has laid bare some disturbing criminal and financial details about Bihar’s sitting MLAs, highlighting a political system where crime, wealth, and power go hand in hand.

Consider this: Out of 241 sitting MLAs analysed from Bihar’s 243-member Assembly, a staggering 158 MLAs (66%) have declared criminal cases against themselves. More alarmingly, 119 MLAs (49%) face serious criminal charges, including murder, attempted murder, and crimes against women.

Of the 241 sitting MLAs whose affidavits were analysed, 66% have criminal cases filed against them. That’s two out of every three lawmakers. And these are not just minor run-ins with the law. Nearly half of them (49%) are facing serious charges, including murder, attempted murder, and crimes against women. Think about that — the people responsible for making the laws are, in many cases, accused of breaking the most serious ones.

Sixteen MLAs have declared murder charges under IPC Section 302. Thirty more are facing charges for attempted murder. Eight are charged with crimes against women. Apparently it is not an aberration, it is a norm.

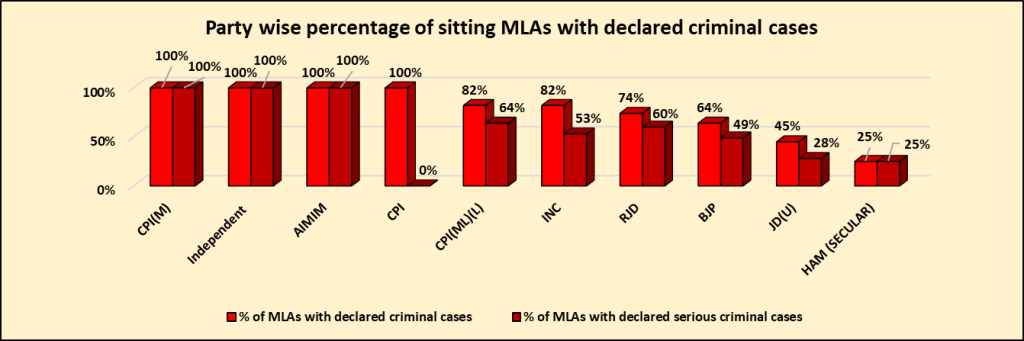

Across party lines

No single political party can claim moral high ground here. Every major party in Bihar is steeped in this pattern of criminality.

• BJP: 64% of its MLAs face criminal cases; nearly half face serious charges.

• RJD: 74% with criminal cases; 60% with serious ones.

• JD(U): 45% criminal cases, 28% serious.

• Congress: 82% of its MLAs have criminal records.

• Smaller parties like CPI, CPI(M), and AIMIM? In some cases, 100% of their MLAs have criminal cases.

And then, there’s money

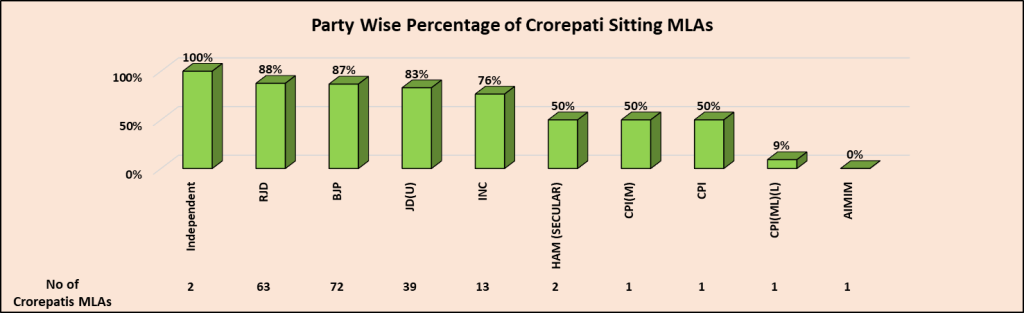

Bihar is said to be a poor state but in the Assembly, the rich don’t just run the show — they own it. Out of the 241 MLAs, 194 are crorepatis—that’s 80%. And the average wealth per MLA—a cool Rs. 4.65 crore.

The total assets of 241 sitting MLAs are Rs. 1121.61 Crores.

Party-wise as many as 72 (87%) out of 83 MLAs from BJP, 63 (88%) out of 72 MLAs from RJD, 39 (83%) out of 47 MLAs from JD(U), 13 (76%) out of 17 MLAs from INC, 2 (50%) out of 4 MLAs from Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular), 1 (50%) out of 2 MLAs from CPI(M), 1 (50%) out of 2 MLAs from CPI, 1 (9%) out of 11 MLAs from CPI(ML)(L) and 2 (100%) out of 2 Independent MLAs have declared assets valued more than Rs 1 crore.

Here’s how it looks party by party:

• JD(U) tops the wealth chart with an average of Rs. 7.08 crore per MLA

• RJD follows with Rs. 5.21 crore

• Congress: Rs. 5.57 crore

• BJP: Rs. 3.51 crore

Even independent MLAs are crorepatis — both of them.

The message is clear: to get elected in Bihar, you either need deep pockets, a criminal network, or both.

The question is when lawmakers walk into the Assembly hall with murder charges pending and crores in their bank accounts, what kind of governance can people expect? And the issue is that it is not just Bihar, the pattern repeats across many Indian states.

Toxic pattern—cough syrup again

Contaminated cough syrup has claimed the lives of around 20 children in Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh Deputy Chief Minister Rajendra Shukla on Tuesday said that 20 children have died after consuming a contaminated cough syrup, while five others are currently undergoing treatment for kidney failure. Among the victims, 17 were from Chhindwara district, two from Betul, and one from Pandhurna.

The children had reportedly been suffering from fever and cold before taking the syrup, branded ‘Coldrif’, which led to symptoms such as vomiting and difficulty in urination. The first death was recorded on September 2. The syrup was manufactured by Sresan Pharmaceuticals, located in Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu.

Investigations by drug control authorities in Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh earlier this month revealed that the syrup contained over 45% diethylene glycol (DEG), a toxic chemical known to cause severe kidney damage and even death. As a result, both states have banned the sale of the product.

In connection with the case, Madhya Pradesh Police arrested Dr Praveen Soni, a government pediatrician from Parasia in Chhindwara, for prescribing the syrup. Authorities have also filed charges against the manufacturer and established a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to further probe the incident.

But this tragedy is not an isolated case. Over the years, diethylene glycol contamination in Indian-made cough syrups has been linked to multiple child deaths. In 2023, DEG-tainted syrups from India were associated with the deaths of 70 children in The Gambia and 18 in Uzbekistan. Similarly, between December 2019 and January 2020, at least 12 children under the age of five died in Jammu after consuming a contaminated cough syrup. Activists claimed that the actual death toll might have been higher.

Beyond contamination, misuse of cough syrups containing codeine—a mild opioid—has also raised alarm. Such syrups can induce euphoria in high doses and lead to dependency, and are not recommended for young children.

In 2023, India’s drug regulator—the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO)—found two syrups manufactured by Norris Medicines Ltd to be toxic. These included a cough syrup and an anti-allergy formulation. Lab tests confirmed contamination with both DEG and ethylene glycol (EG)—the chemicals involved in fatal incidents in The Gambia, Uzbekistan, and Cameroon in 2022.

According to CDSCO’s laboratory testing, Trimax Expectorant contained 0.118% EG, while the allergy medication Sylpro Plus Syrup had 0.171% EG and 0.243% DEG. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the safe limit for these substances, based on international standards, is no more than 0.10%.

Despite repeated promises of reform from regulators, contaminated syrups continue to surface. This recurring issue highlights the challenges of a fragmented pharmaceutical market and an overstretched regulatory system, which struggles to monitor the widespread production and over-the-counter sale of low-cost, often unapproved, medications by smaller manufacturers, say activists