Chhattisgarh’s Achanakmar Tiger Reserve has a memorial dedicated to firewatcher Maiku Gond, who was killed by a man-eating tigress 73 years ago. The story can trigger discussion on wildlife conservation at a time when the reserve has poor tiger numbers, writes Deepanwita Gita Niyogi

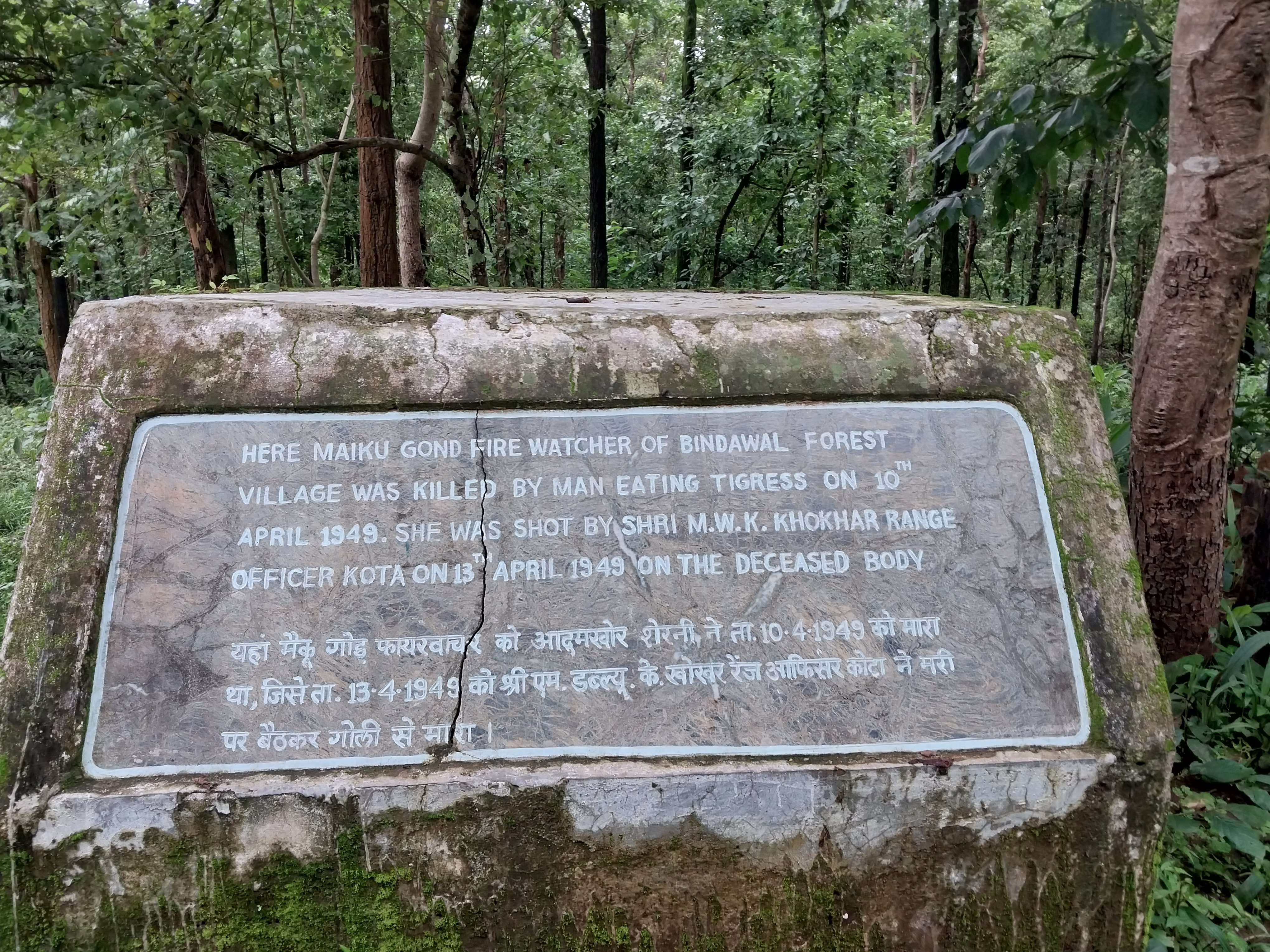

Tiger tales are fascinating. The Achanakmar Tiger Reserve, 186 km from Raipur, has one such story. Here, a memorial is dedicated to firewatcher Maiku Gond, who was killed by a man-eating tigress on April 10, 1949. The animal was killed three days later.

Achanakmar, which was declared a tiger reserve in 2009, is spread over 914.017 sq km. Though situated in Chhattisgarh, the reserve is well linked to Kanha and, maintains connectivity with Pench as well as Bandhavgarh in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh. There were five tigers in Achanakmar, according to the Status of Tigers, Co-predators and Prey in India 2018 report.

The origin of the name Achanakmar is fascinating. Once a fight broke out between two groups leading to someone slapping another all of a sudden. Thus, the name Achanakmar or sudden slap stayed on.

Standing near Maiku’s memorial, Brijbhushan Manikpuri, beat guard of Chhaparwa range in Achanakmar Tiger Reserve, said when it was a territorial division, Achanakmar came under the Kota range. “In 1949, the place was densely forested and plenty of tigers roamed about. After Maiku lost his life, MWK Khokhar, who was then the range officer of Kota, killed the animal from a maachan or platform erected in a tree. The memorial dedicated to Maiku is now called Maiku math,” Manikpuri added.

Revisiting history

A few kilometres from the memorial, lies Maiku’s forest village, Bindawal. Elderly Shivaram Potta, a Gond Adivasi man, fondly recalled his maternal uncle. Maiku was a fire watcher along with another man called Parsadi Maravi. Both used to roam the jungles trying to protect it from fires.

“The day Maiku was killed, Parsadi somehow managed to escape. Later he was promoted by the department. The tigress attacked when Maiku was clearing dry leaves piled up along the road. The animal dragged the body to a nearby nullah. Khokar sahib was informed. When the animal came near the spot, she was shot.”

Potta informed that the tigress which killed Maiku 73 years back was injured in the leg and came from the jungles of Lamni, a range in the core area. In stark contrast to yesteryears, today there are only five tigers in Achanakmar and they are spotted rarely.

Tigers in Achanakmar disappeared one by one. According to Potta, hunting wiped off the animals. Hunters used to come from outside. Sometimes, they travelled in a group with drums, shouted loudly and then killed tigers when the animals tried to escape from the commotion.

About 10 minutes into the conversation with Potta, Maiku’s grandson Jaleshwar Siyam arrived. The young man is a foot guard who travels 10 km daily. “Like my grandfather I joined as a fire watcher and have been employed in the forest department for 11 years. I used to douse fires and have spotted tigers once or twice.”

Siyam informed that there have been incidents of tigers causing injury to humans in Achanakmar. Two cases of injury occurred in the past two years but thankfully there were no deaths. But guards keep moving, sometimes together, for safety.

Just like the olden days, fires break out even now. From 2020-2021 to 2022-23, there have been 1190 cases of fire over 390.981 hectares. A total of 327 fire watchers have been deployed to keep an eye on the valuable forest.

Relocation a distant dream

Bindawal, where Maiku’s story is still fresh in memory, is one of the 19 villages in the core area of Achanakmar where residents rely on solar power and put up with wildlife conflict. Talks of relocation have been going on for a decade in Maiku’s village but nothing has come of it.

In Bindawal, people are either into farming or work as labourers for the forest department. Potta revealed that the gram sabha consented to the idea of relocation 10 years back. However, the residents of Bindawal could not shift as outsiders started encroaching on the land where they wanted to settle down. There is also a lack of facilities in Bindawal. The school in the village is till Class 5 and those who wish to study further go to Chhaparwa, about three km away, which thankfully has a high school.

“Only God knows how we live here. A health centre was being constructed but stopped midway. Houses under the Indira Awas Yojana cannot be built inside tiger reserves. The tigers may have vanished, but what about elephants? They pose a threat to crops and lives,” Potta said.

Field director of Achanakmar Tiger Reserve, S Jegadeesan said the relocation process for Bindawal village is on, but land for the displaced has to be in revenue pockets. If not available, the department will have to identify forest land. There are 19 villages in the core area and of these four villages want to stay back. Those willing to shift can either opt for two hectares of land or Rs15 lakh as cash compensation. Those holding lands will get lands in return and the landless will receive cash.

On his part, Potta made it clear that the residents of Bindawal want to leave as they want the forest to remain intact. With almost 45 percent of its area under forest, Chhattisgarh has good forest cover, but the state has only 19 tigers at present. The figure is down from 46 counted in 2014.

While a story like this can attract tourists to visit Achanakmar, it also gives an opportunity to work on wildlife protection, improve forest conservation, offer suitable relocation packages to villagers ready to move and carry out forest fire prevention.