In the backdrop of a difficult relationship with China, India has to strike a tricky balance between the emerging US and China-led blocs. Resolution of another friction point in Ladakh has given India more elbow room in finding its way around. A report by Riyaz Wani

In a sign that the lingering stand-off between India and China may be finally coming to an end, the two countries have completed disengagement from the Gogra-Hotsprings border area in Ladakh after reaching a consensus in the 16th round of India-China Corps Commander-level meeting.

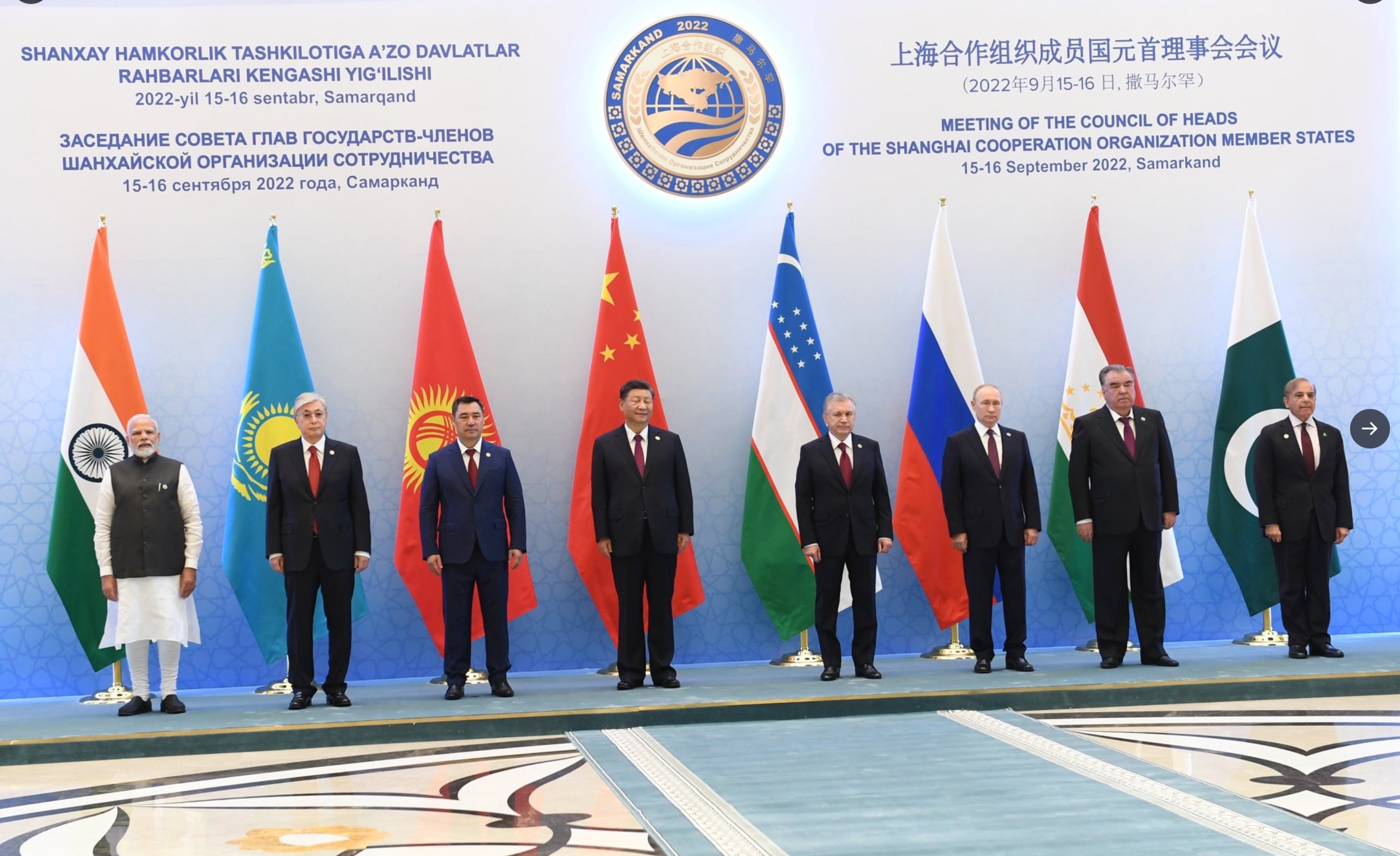

The move came just ahead of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting in Uzbekistan which was held on September 15-16. The meeting was attended by the leaders of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) member countries including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif.

India and China have been engaged in a bitter standoff ever since the Chinese army staged incursions across the Line of Actual Control in multiple areas in April-May 2020. The situation came to a head in May 2020 when 20 Indian soldiers lost their lives during a scuffle along the border. Ever since, multiple Corps Commander-level talks and a few meetings between the foreign ministers of the two nations yielded little result.

Meanwhile, the People’s Liberation Army has enhanced its military profile along the border by deploying thousands of its soldiers and equipment. In recent years China has reportedly more than doubled its total number of airbases, air defence positions and heliports near the Indian border.

The problem in the negotiations so far has been that China has been loath to go back to the status quo ante and has asked for mutual withdrawal. The incursions in the first place have been staged by China and the communist giant was not ready to vacate it unless India also withdrew from a portion of the border on its side of the LAC. But New Delhi could hardly afford to do it, not least because it considers the area its own. Doing so would have been politically costly for the BJP government at the centre which was already facing severe flak for vacating Kailash ranges as part of its Pangong Tso agreement. But through sustained negotiations they have finally found an amicable way out along two points.

Last year, in a first breakthrough in talks, India and China pulled back their troops from the south bank of Pangong lake area in eastern Ladakh following their agreement for “synchronised and organised disengagement”. But subsequently, there was no progress on the other three points of friction – Galwan Valley, Depsang, Gogra-Hot Springs. But Gogra-Hot Springs has been resolved again. There is hope that, like the two friction points so far, the two countries will find a diplomatic solution to the stand-off at Galwan Valley and Depsang also, sooner than later.

Over the last close to three years, the stand-off along the LAC has become a high stakes war of nerves between the two countries. But New Delhi approached the situation very cautiously and waited if China’s intermittent statements of reconciliation were translated into action. There was also a realization that the complete de-escalation would be a long haul. This seems to have paid off for now.

It remains to be seen whether the two nations will be able to reach a similar agreement on Galwan Valley and Depsang also.

Opposition to agreement

The agreements on Pangong Tso and Gogra-Hot Springs have invited a fair degree of flak from the political parties and some analaysts who have viewed the mutual withdrawal as surrender to China.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi slammed the centre and alleged that the government had ceded thousands of kilometres of Indian territory to China.

“Mr Modi and his minions have ceded thousands of kilometres of Indian land to China,” Gandhi asked. “When exactly are we getting it back.”

The critics have also alleged that as part of the truce, buffer zones were created in which neither side was allowed to patrol their troops. But the locals and elected representatives of Ladakh have also claimed that these zones have been created in areas previously under Indian control.

Konchok Stanzin, an elected councillor from the region, said that the Indian army is vacating areas which were not disputed at all, while Chinese troops are stationed in the areas traditionally patrolled by India. He also claimed India had already ceded land during a 2021 agreement to withdraw from areas around Pangong Tso lake.

“We seem to be giving our land happily. If India’s approach remains the same, we are going to lose more land,” he said. “Our concern is no longer only about Chinese incursions but voluntarily giving up our own land.”

End of standoff?

That said, the disengagement along two friction points shall go a long way to calm the LAC which over the last three years had brought Indian and Chinese armies eyeball to eyeball and on the brink of war. This will also go some way to take some pressure off the Indian Army which was stretched along the LAC, with harsh winter making it even more difficult.

However, India’s military brass remains deeply skeptical about China’s intentions. Speaking at a recent event organized by Bharat Shakti, Army chief General Manoj Pande said there are still two friction points at the LAC in eastern Ladakh that India and China need to move forward.

“I am sure we will be able to find resolution towards these two friction points. That is our immediate aim to disengage from these friction points before we look at the next step of de-escalation, which will involve pullback by troops and tanks,” he said

Similarly, speaking at the 49th annual management convention of the All India Management Association, Navy Chief Admiral R. Hari Kumar said that China remains a formidable challenge and has increased its presence not only along India’s land borders, but also in the maritime domain by leveraging anti-piracy operations to normalise its naval presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

More geopolitical space

The disengagement along the two friction points, however, has opened up more geopolitical space for India. Despite a difficult relationship with China, India has maintained its strategic autonomy and independent foreign policy. During the ongoing Ukraine war, India hasn’t entirely gone along with the west’s line and maintained its age-old relationship with Russia. India has continued to buy cheap oil from Russia despite western sanctions.

India has also tried to strike a tricky balance between the emerging US and China-led bloc. It is true that China has become a far bigger power than India, both economically and militarily. So much so that China is now seen as a credible rival to the US which has otherwise been the sole superpower since the break-up of the USSR in 1989.

India’s choices are thus stark: It has to either cooperate with China in a subservient position. Or try standing up to Beijing by entering into a formal alliance with the US and becoming an active member of Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – a grouping comprising the US, Japan, Australia and India – also called Asian NATO. Both choices have their consequences, more detrimental than favourable to India. So, New Delhi has so far been chary of committing itself to either side so as to maintain its strategic autonomy. This would involve negotiating its relations with Beijing and also engaging with the US. And going by the cautious and mature handling of the LAC standoff, the union government has been doing a good job so far.