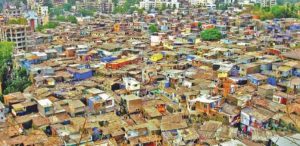

Every day countless families struggle to keep a decent roof over their heads. There are millions of low-income families, who live in overcrowded, unsafe spatchcock dwellings, crammed between dusty paths and open sewers with virtually no sanitation, environmental risk factors and lack of even the barest infrastructure. These are usually socially homogenous encampments where unskilled poor live among themselves, disconnected from others, making it harder for them to access mainstream economy.

Every day countless families struggle to keep a decent roof over their heads. There are millions of low-income families, who live in overcrowded, unsafe spatchcock dwellings, crammed between dusty paths and open sewers with virtually no sanitation, environmental risk factors and lack of even the barest infrastructure. These are usually socially homogenous encampments where unskilled poor live among themselves, disconnected from others, making it harder for them to access mainstream economy.

The dwellers experience exclusion, discrimination and lack of hope to access adequate and affordable housing. They are under constant threat of being evicted without notice. A single eviction could destabilise multiple blocks, not to account for the block to which the family is begrudgingly relocated. Most of their possessions — water containers and tents among others — are periodically steamrolled by eviction agencies.

While we have been able to fight poverty relentlessly and continue to record improvements, homelessness remains a big challenge A decent habitat and shelter environment for the poorer sections of society can not only contribute towards their well-being and real asset creation, but also catalyse overall economic growth. It is thus critical to recognise housing investment as a basic, fundamental building block of economic activity. There is little more critical to a family’s quality of life than a healthy, safe living space. Priority for housing is higher than education and health. Sustainable and inclusive housing solutions, indeed, could bolster economic growth quickly and efficiently.

Landlessness and the lack of secure property rights among the poor are among those inequities that perpetuate poverty, hold back economic development and fan social tensions. Demographic shifts, combined with poor or non-existent land ownership policies and insufficient resources have resulted in a surge of slum creation and further deteriorated living conditions.

Hernando de Soto in his book The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else observed, “The hour of capitalism’s greatest triumph,” declares the famed Peruvian economist, “is in the eyes of four-fifth of humanity, its hour of crisis.” Soto explains that for many people in the developing world, the land on which they live is their only asset. If that property is not publicly recognised as belonging to them, they lose out that is, when men and women do not receive recognised legal rights to their land and can, thus, easily be displaced without recourse — development efforts flounder, undermining conservation efforts, seeding injustice and conflict and frustrating efforts to escape poverty.

The lack of official land titles is a major impediment to the acquisition of housing finance. People do not have documentary proof of being owners of the piece of land on which they live. Many low-income villagers have owned their land for generations. The United Nations has estimated that more than 70 per cent of the world’s population lives without any formal

acknowledgement of ownership of land. That is both a human and economic problem. Without the security of ownership, poor often invest little in their homes, result being a fragile home that cannot withstand natural disasters, including floods. Whereas, when people have secure land rights, they invest in improvement projects, work more hours without fear of land theft and are more likely to take loans using their new property as security.

Lack of ownership right deprives people of basic amenities. Once titled, they can obtain access to several Government benefits. Even a small plot can lift a family out of extreme poverty. Land ownership is often the bedrock of other development interventions, like owning land boosts nutrition, educational outcomes and gender equality. The converse is equally true.Millions of urban citizens remain “off the map” failing to extend basic services to slum residents by using the concept of “opportunistic infl ux” — the idea that the provision of services might encourage greater migration from rural areas, thereby paradoxically increasing urban deprivation.

There is little more critical to a family’s quality of life than a healthy and safe living space. However, this section of India’s poor lives in inhuman conditions and is often under the threat of displacement, harassment and arrest. Over the last decade, India has substantially expanded its net of welfare policies, aimed at lifting millions from poverty. It seems that the time has come for making ‘right to shelter’ a reality. Priority for housing ought to be higher than education and health.

Challenges for India are daunting and homelessness has become a powerful monster. An estimated 65 million people, or 13.6 million households, are housed in urban slums, according to the 2011 Census. It also showed that an additional 1.8 million people are homeless. Recent estimates by the Ministry of Rural Development and Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs indicate a housing shortage of nearly three crore units in rural areas and 1.2 crore units in urban areas. Today, estimates of India’s slum population range from 65 to 100 million, comprising 17-24 percent of the country’s urban residents. In Mumbai, India’s financial capital, about 52.5 percent of the population lives in slums, crammed in just nine percent of the city’s total geographical area.

The grim aspect of the housing scenario is that the number of homeless is huge despite the fact that its composition of urban population is much lower compared to other countries. According to the World Bank, urban population, as a proportion of the total population in 2015, stood at 86 per cent in Brazil, 56 per cent in China, 54 per cent in Indonesia, 79 per cent in Mexico, 82 per cent in South Korea and 31 per cent in India.

By the accepted definition of slum (minimum 60 households), more than 2,500 Indian cities have slums; overall, there are 33,500 slums and the total population stands at 65.5 million. About 90 per cent of the residents have electric power and 56 per cent have access to water. These figures pose a huge challenge for planners. Affordable housing has assumed great importance because it generates direct and indirect employment in the medium-term and sustained consumption in the long-term. A 2014 study by the National Council of Applied Economic Research indicated that every additional rupee of capital invested in the housing sector adds 1.54 to the GDP and every 1 lakh invested in residential housing creates 2.69 new jobs in the economy.

The lack of official land titles is a major impediment to the acquisition of housing finance. People do not have documentary proof of being owners of the land on which they live. Many low-income villagers have owned their land for generations. Landlessness and the lack of secure property rights are among those inequities that perpetuate poverty hold back economic development and generate social tensions.

Demographic shifts, combined with poor or non-existent land ownership policies, have spawned huge slums across the country.

For most of India’s poor and the vulnerable, secure property rights, including land tenure, are a rare accessible luxury. Land tenure determines who can use land, under what conditions and for how long. Tenure arrangements may be based both on official laws and policies, and on informal customs. There was a time when landlessness affected a smaller chunk of the population. However, the number of landless people has been rising. The ones without land joined the ranks of the worst ones in extreme poverty and the task of poverty alleviation became even more difficult. Considering the links between landlessness and poverty or the need to score better successes against poverty, it is important to put a hard brake on the process of becoming landless. Land is a very price-sensitive commodity and its current shortage in most city-centric areas is an impediment towards creating affordable housing in urban areas where it is most needed. Some suggestions from experts can serve as useful markers for policy-makers while designing Government programmes for housing.

♦ Governments should improve the legal and regulatory environment related to housing and increase the supply of affordable, legal shelter with tenure security and access to basic amenities.

♦ Government must undertake physical upgradation of informal settlements. Informal urban settlements can be provided with infrastructure by widening roads, creating playgrounds, laying sewage pipes and installing water taps and toilets. These services create a high-level of tenure security without a formal change of legal status and encourage local improvements which can transform these slums into livable habitats.

♦ Making in situ improvements to these settlements would allow slum residents to remain connected to their own critical social and economic networks.

♦ Government can consider converting under-utilised urban land for affordable housing and economic development with realistic standards for development. It can recognise semi-formal titles of land as workable collateral for home improvement loans.

♦ Government should actively explore endowing slum dwellers with land rights for residential use that are inheritable, mortgageable and non-transferable. Endowing them with mortgageable titles can open the gates for improving health, education and employment.

♦ Corporate should be encouraged to invest in slum improvement programmes. The Companies Act 2013, which requires companies to give at least two percent of profits towards Corporate Social Responsibility, has already been amended to include slum area development and housing. Government can consider mandating a specific percentage for slum development.

In response to the non-availability of tangible collateral from low-income households, as required by the formal financial sector, a new stream of lending has emerged, called ‘housing micro-finance’. Institutionalised micro-finance systems have come up with innovative solutions. These draw on the best practices in micro-finance but remain adapted to the classical housing finance paradigm. This has been highly successful wherever Governments are offering long-term tenancies and shared-ownership housing in a supportive context. But the sector is still in need of a more sustainable business model to grow.

In response to the non-availability of tangible collateral from low-income households, as required by the formal financial sector, a new stream of lending has emerged, called ‘housing micro-finance’. Institutionalised micro-finance systems have come up with innovative solutions. These draw on the best practices in micro-finance but remain adapted to the classical housing finance paradigm. This has been highly successful wherever Governments are offering long-term tenancies and shared-ownership housing in a supportive context. But the sector is still in need of a more sustainable business model to grow.

One major cause of India’s aggravating problem is the weak legal structure for handling rental housing. According to census data, the share of rental housing in total housing fell from 54 per cent in 1961 to 28 per cent in 2011. In 2011, despite a severe shortage of rental housing, 11.09 million urban properties remained vacant across India. In most states in India, traditionally, rent control laws have disproportionately protected the tenant. Consequently, we have the paradoxical situation of unsatisfied demand for rental housing while many units lie vacant. It is time the government puts rental housing to use .The share of rental housing in overall housing has been steadily declining. According to census data, it dropped from 54 per cent in 1961 to 28 per cent in 2011. There is clearly need for replacing the current rent control laws by a modern tenancy law, which would give full freedom to tenant and owner to negotiate the rent and the length of the lease. Rules with respect to eviction also need to be reformed to restore balance between the rights of the tenant and the owner.

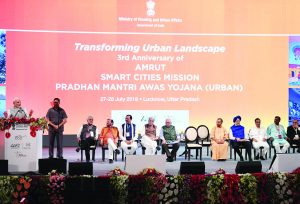

India’s flagship housing programme Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) has not been able to make substantial dent. The PMAY is a revamped scheme that was earlier called the Indira Awaas Yojana (IAY) The IAY was launched in the 1980s and gave the rural poor a cash incentive of 70,000 to build a home. The new scheme offers monetary subsidies of 1.2 lakh to 1.3 lakh for constructing rural houses and 1.3 lakh to 2.6 lakh for urban houses. It includes slightly better off lower-middle income groups who have never owned a home and provides interest subsidy on funds borrowed for the acquisition of houses. The scheme has done well by making it inclusive regardless of size of house or loan, but it limits the support from government to a ceiling subject to other norms

The housing sector demands high level of creativity .The conventional bureaucratic approach and thinking and existing laws can merely scratch the problem.

letters@tehelka.com