Amid a storm of allegations, counterclaims, and political drama, India’s electoral system finds itself under intense scrutiny. The recent controversy surrounding alleged voter roll manipulation has exposed potential cracks in the foundation of India’s electoral democracy—raising questions not just about technical safeguards, but about trust in the Election Commission itself.

It began when opposition leaders accused the Election Commission of India (ECI) of facilitating or ignoring attempts to delete thousands of voter names. The slogan “vote theft” quickly became a central rallying cry for the Opposition, sparking a wider debate about electoral fairness.

Although the ECI has dismissed the accusations as baseless, demanding evidence via affidavit, it has since introduced new digital verification mechanisms, including a mandatory OTP (one-time password) system linked to Aadhaar-verified mobile numbers. The new e-signature feature on the ECINet portal and app—rolled out shortly after the Aland controversy—requires identity verification for those seeking to add or delete names from the voter list.

The ECI insists this upgrade was not a reactive measure, but critics aren’t buying it, charging that the Commission is “being clever by half,” indicating a serious vulnerability.

The controversy deepens as the Karnataka CID alleges that the ECI has failed to provide critical data—IP logs and phone records—that could aid the investigation into who attempted the mass deletion. There is a question: if no wrongdoing occurred, why was an FIR filed?

Former Chief Election Commissioners agree that the ECI’s response has been inadequate. S.Y. Quraishi criticized the Commission for its aggressive dismissal of the Opposition’s concerns. Another former CEC, O.P. Rawat, argued the Commission broke with long-standing tradition by not immediately launching a credible and transparent inquiry into the complaints.

While the ECI maintains that votes cannot be deleted online without physical verification, the debate isn’t about procedural safeguards—it’s about public perception and institutional accountability. The introduction of tech features like Aadhaar-linked verification may close one loophole, but without transparency, scepticism will persist.

With assembly elections around the corner, the fallout from this controversy could be significant. As “vote theft” becomes more than just a slogan, the ECI must reckon with the deeper issue: restoring trust in the very process it was meant to protect.

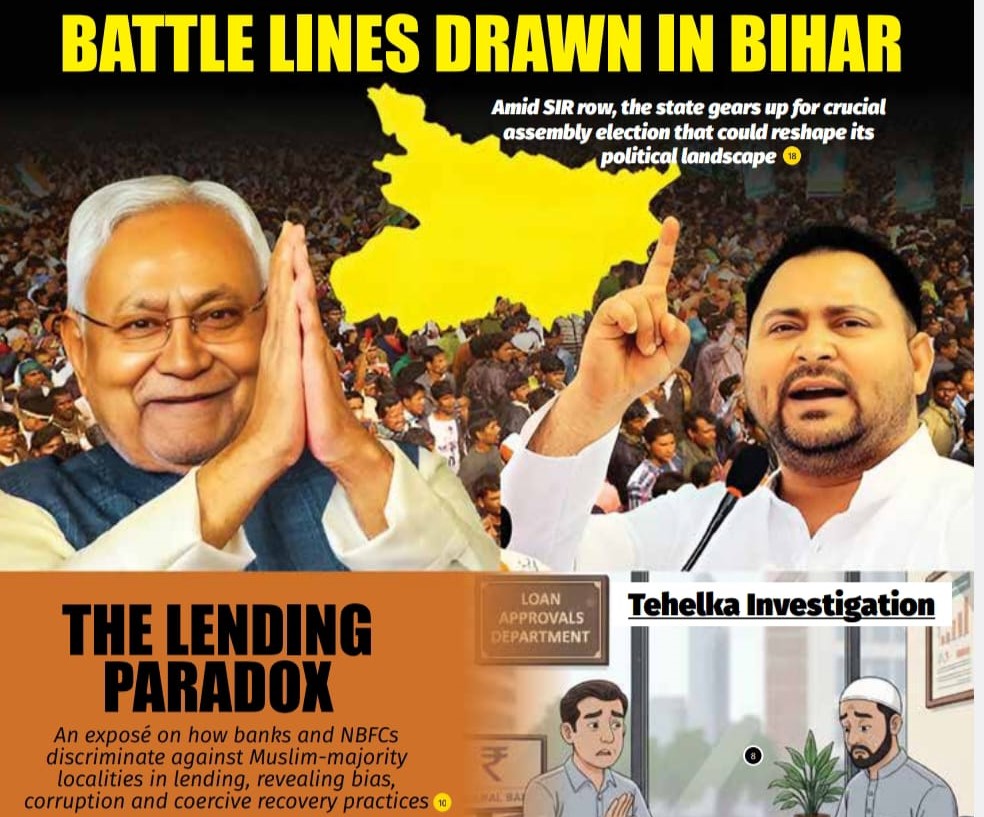

Meanwhile, Tehelka’s cover story ‘Battle lines drawn in Bihar’ is about how, amidst the SIR row, the state is gearing up for the crucial assembly election that could reshape its political landscape, where CM Nitish Kumar and challenger Tejashwi Yadav square off, with Prashant Kishor looming as a wildcard.

Also, our Special Investigation Team (SIT), in its latest probe, has unearthed how banks and NBFCs discriminate against Muslim-majority localities in extending credit. The investigative story ‘The lending paradox’ is an exposé on how banks and NBFCs discriminate against Muslim-majority localities in lending, revealing bias, corruption, and coercive recovery practices.