Tehelka’s SIT investigation into the alleged availability of the banned Chinese Manjha — a glass-coated string used for flying kites that endangers human lives — in markets across Agra, Kolkata and Delhi has reveals a disturbing reality that the ban has had little to no effect.

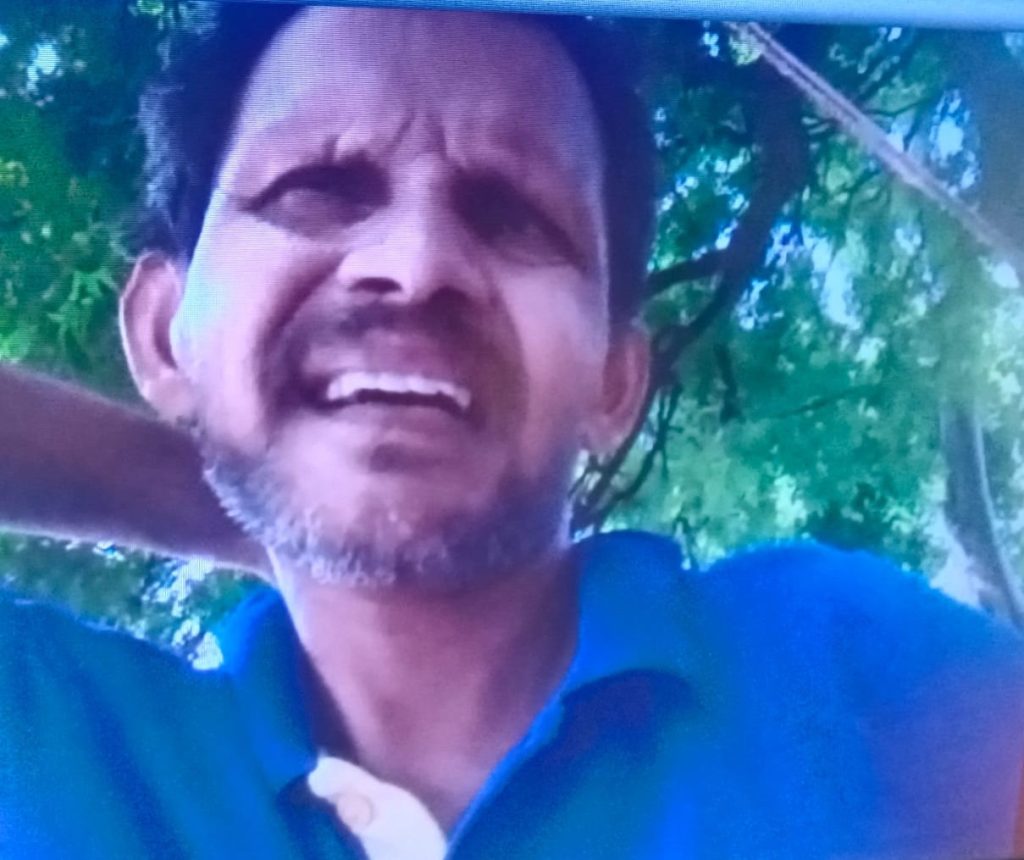

“I think you are recording our conversation. Are you doing a sting! If you want to buy Chinese Manjha from me, just buy it. Why are you asking so many questions? It feels like you’re recording me. Please make sure I don’t get into trouble,” says Nasir Khan, alias Munna, a kite supplier from Agra, Uttar Pradesh, while selling banned Chinese Manjha (glass-coated kite string) to the Tehelka reporter.

“I have supplied 5 kg of ganja [marijuana], a banned drug, from Kolkata to Bangalore through my courier. I wrote ‘medicine’ on the packet, and it passed through without any checks. In the same way, I will send Chinese Manjha from Kolkata to Delhi using my courier service. Chinese Manjha is also banned in Kolkata, but it is sold clandestinely to selected customers. I can supply it to Delhi on a regular basis,” said Rajesh Singh (name changed), another Kolkata-based supplier of banned Chinese Manjha, during the Tehelka investigation.

“Shyam Kumar, a supplier from Shahdara, Delhi, is ready to supply Chinese Manjha at Rs 500 per roll. However, he is wary of meeting unknown people and does not want to talk over the phone. He said he’s willing to deal through me,” said Javed Khan (name changed), from Delhi, while speaking to Tehelka.

In India, kite-flying holds significant nostalgic and sentimental value. However, the unchecked use of illegal glass-coated strings for flying kites has proven fatal for residents. Chinese Manjha, made from nylon thread that feels like plastic, is thin and helps fly kites easily. Experts suggest that while it is locally manufactured, the primary ingredient (synthetic polypropylene) is sourced from China.

India witnesses numerous deaths and injuries from Chinese Manjha every year. These instances typically spike in the weeks leading up to Independence Day and Makar Sankranti, when more people head to their rooftops to fly kites in the capital. According to police records, several people have died after their throats were slit by the string. The damage is not limited to humans, with animals also falling victim, and the environment also getting impacted. Over the decades, incidents involving Chinese Manjha have become a growing menace. As a result, in 2017, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) prohibited the sale, manufacturing, and supply of glass-coated threads across the country.

Yet, despite the ban, Chinese Manjha remains in high demand in India. It is cheaper and more effective in cutting competitors’ kites compared to Indian Manjha. Numerous arrests have been made across the country for selling the banned and potentially lethal string, but despite the claims of strict action by the police, the sale continues.

Tehelka conducted an in-depth investigation into the alleged sale of banned Chinese Manjha in Agra, Kolkata, and Delhi. The investigation found that the ban largely remains on paper. Kite suppliers in these cities were caught on camera selling the prohibited string. The first stop of the investigation saw a Tehelka reporter meet Nasir in Agra, posing as a client seeking a regular supply of Chinese Manjha for his kite business in Delhi. Nasir arrived in Agra with the illegal string to meet the reporter.

Reporter- Manjha kaunsa hai aapke pass ?

Nasir- Wahi hai jo aapne mangaya hai

Reporter- China ka?

Nasir- Plastic ka boltey hai..China ka.

Reporter- Boltey to china ka hi hai, nylon wala, plastic wala, wahi sheeshey wala

Nasir- Haan wahi wala.

[In this matter-of-fact conversation, Nasir nonchalantly confirms that he has brought the Chinese Manjha our reporter had asked for. It becomes clear that Chinese Manjha is also known by other names like nylon wala, plastic wala, and sheeshe wala.]

We told Nasir that we wanted a regular supply of Chinese Manjha from Agra to Delhi, as the ban on Chinese Manjha is much stricter in Delhi than in Agra. Nasir replied that he knew a supplier in Jaipur, Rajasthan, who could provide a regular supply of the banned Manjha. He mentioned that he had brought a sample of the Chinese Manjha for us, and since he has our contact number, he will inform us whenever he receives more

Reporter- Dekho aisa hai Delhi mein to hai nahi ye.

Nasir- Ban hai.

Reporter- Poore India mein ban hai….iski supply chahiye zyada.

Nasir- Dekhiye mein to chota mota dukandaar hoon.. abhi aap ye le jaiye, abhi iska ek distributor hai Jaipur mein.

Reporter- Kaun hai Jaipur mein?

Nasir- Ye mujhe maloom karna padega.

Reporter- Distributor hai Jaipur mein…China manjhe ka ?

Nasir- Haan

Nasir- Hum to chote mote dukandar hai, 1-2 lekar bechtey hain, aap chahe se le lijiye..aage se aapka number mere pass hai hi, jaise maloom padega aapko bata dunga..

[As the conversation between the Tehelka reporter and Nasir Khan continues, the supplier begins to reveal more details about the banned Chinese Manjha network. It emerges that despite the ban, the Chinese Manjha trade remains active, with larger players possibly active across India.]

In this exchange, our reporter seeks to confirm Nasir’s identity and the location of his shop in a key marketplace. As Nasir, casually shares his alias “Munna,” it is revealed how he operates in a close-knit, informal network.

Reporter- Aapki dukaan wahi hai na maal ke bazaar mein ?

Nasir- Haan.

Reporter- Kiske naam se hai?

Nasir- Mere hi naam se hai.. Nasir bhai ke naam se pooch lena.

Reporter- Poora naam kya hai?

Nasir- Nasir bhai.

Reporter- Khan, Ali kuch nahi?

Nasir- Haan…Khan laga lena.

Nasir (continues)- Aapka shubh naam kya hai?

Reporter- Mera naam Aamir Ali…aur aapka Munna….Munna ke naam se patang ki dukaan hai na?

Nasir- Ji.

[The conversation subtly reveals how Nasir, popular as Munna, operates with an informal, easily recognizable identity in the kite business. This perhaps is a pointer to the fact that sellers in the Chinese Manjha trade rely on local recognition to stay under the radar.]

Our reporter continues probing Nasir about the variety of Chinese Manjha he supplies. Nasir, while maintaining a low profile, insists that his stock is limited to a single type, a ‘gold’ variety, subtly conveying his cautious approach in dealing with customers.

Reporter- Filhaal batao manjhe kaun kaun se hain..?

Nasir- Ismein to ‘gold’ hi hai bas.

Reporter- Gold ki ek hi variety hai bas, aur kuch nahi hai..?

Nasir- Hum to ek-ek –do-do lekar hi bechtey hain, bhai.

[Nasir’s reluctance to disclose more than a single variety of Chinese Manjha perhaps indicates that smaller suppliers like him carefully manage their operations, staying within limits to avoid attention.]

When asked as to what quantity of Chinese Manjha he can supply to us on regular basiS, Nasir said he will check from his supplier and let us know. At present, he said, he had only one roll of Chinese Manjha.

Reporter- To ye batao hame kitna maal mil sakta hai ?

Nasir-Ab ye to pooch kar bataunga aise kaise bata sakta hoon.

Reporter- Aap kitna de saktey ho?

Nasir – Ek hi hai mere pass to.

Reporter- Abhi nahi aagey?

Nasir- Mein aapko pooch kar bata dunga.

[Nasir’s cautious approach highlights his reluctance to reveal details without confirmation. So, obtaining banned goods requires both persistence and patience, as the suppliers are careful about their dealings.]

Nasir became suspicious after our reporter posed a series of questions about Chinese Manjha to him. He pleaded that as his kids are very young, he didn’t want to get into any trouble. After getting assurance from the reporter about his safety, Nasir told us that he had brought a sample of Chinese Manjha for him, and demanded money for that.In a candid exchange, our reporter questions the pricing of the banned Chinese Manjha, probing whether Rs 600 is excessive.

Reporter- Filhal dikha do kaisa hai maal ?

Nasir- Ab aisi baat to nahi hai sir…ye laye hain.

Reporter- Kya baat kar rahe ho?

Nasir- Mere bhi chote chote 2 bacche hain.. aisi baat to nahi..koi darne wali baat.?

Reporter- Koi baat nahi hai aap kyun pareshan ho rahe ho. Suno manjha yahin dikhaogey ya kahan dikhaogey.?

Nasir – Yahan dekh lo aap paise de do?

Reporter – Mujhe paise bata do kitne hue?

Nasir- 600 rupiye de do mujhe aap.

Reporter- 600 rupees zyada nahi hai ?

Nasir- Tumhare liye aaya hoon mein yahan pe..ap mera petrol de dena..50 rupees aur de dena bhai. Doosre ki gadi lekar aaya hoon.

[Nasir’s concern over potential risks subtly surfaces, but the discussion swiftly returns to the financials. While justifying the price of Rs 600 he had quoted for the Manjha, Nasir citespersonal effort and costs he’d incurred in making the delivery, including petrol expenses.]

In this conversation, the reporter seeks clarity on the immediate availability of Chinese Manjha and the possibility of securing a consistent supply. Nasir, with limited stock at the moment, reassures the reporter that he can arrange future supplies and stay in contact for updates.

Reporter- Mujhe ye batao mujhe kitna maal mil jayega aapse abhi?

Nasir- Sir mere pass to abhi ek hi hai..aagey hoga to aap ko de dunga.

Reporter- Mujhe chahiye lagatar supply.

Nasir- Mere pass number to hai hi…mein aapko pooch kar bata dunga.

[Nasir admits to a temporary shortage but promises to source more soon. It has come to fore that in such clandestine markets, uncertainty of supply is a recurring theme.]

Now, Nasir asked our Delhi address and recommended a kite supplier from Jaffrabad or Nangloi, Delhi, who can supply Chinese Manjha to us in Delhi itself.

Reporter- Accha patange kaun kaun si hai aapke pass ?

Nasir- Patangey sab milengi..panni ki kagaz ki sab milengi..Delhi mein kahan hai aapki dukaan ?

Reporter- Delhi mein Mayur Vihar..Jamna paar.

Nasir- Acha wahan Jaffrabad mein bhi to hai.To Jaffrabad mein aap us se le lena Raz se, Lalu se, unpar mil jayega sab.

Reporter- Chinese manjha hai unke pass ?

Nasir- Hoga shayad.

Reporter- Aapke jaankar hain?

Nasir- Mere khayal mein Nangloi mein ho shayad.

[Nasir highlights multiple locations for obtaining kites, hinting at the underground market’s reach. Knowing the right contacts is crucial in navigating these illicit trades, ensuring access to restricted products.]

After a series of question from the reporter, Nasir again became suspicious and asked us whether we are recording him. After being assured that he is not being recorded, Nasir told reporter that he is taking Chinese Manjha from a supplier.

Reporter- Ye batao aapki supply kahan hai. Kaunse area se hai ?

Nasir- Hum to local hain, 10-20 rupees khol ke bechtey hain.

Reporter- Aapki supply kahan se hai, kahan se aata hai aapke pass ?

Nasir- Ek distributor dene aata hai..arey aap abhi recording kyun kar rahe ho..?

Reporter- Arey nahi..

Nasir- Dekho meri baat suno mein abhi dukaan se uthkar aaya hoon, aap mujhe record kar rahe ho ?

Reporter- Dekho daro mat ye dekho maine ander kar liya

Nasir- Nahi aap itna kyun pooch rahe ho.. aapne kaha patang ka…Baluganj se aaya hoon..

Reporter- Chalo chodho.

[Nasir’s reluctance to disclose information underscores the secrecy inherent in this trade. It emerges that in such dealings, maintaining a delicate balance between openness and caution is vital for both buyers and sellers.]

Third time again, Nasir raised question whether he is being recorded by us? This time, he asked us to swear on god that we are not recording him. He said we are just dilly-dallying and not serious in buying Chinese Manjha. Nasir became suspicious of us because we asked so many questions to him.

Nasir- Ab sir ye to aap formality poori kar rahe hain…aapko lena wena kuch nahi hai..

Reporter- Aisi baat nahi

Nasir- To aap itni cheezein kyun pooch rahe ho, ye bataiye aap…aap mujhe apna address de do mein aapke pass khud aaonga Mayur Vihar, poora address de do

Reporter- Accha likho.

Nasir- Aap likhkar de do aapke pass pen to hoga.

Reporter- Whatsapp par likh lo mobile kaunsa hai aapke pass.

Nasir- Aap likhar kar send kar do mujhe.

Nasir- Arey nahi bhai.

Reporter- Arey lo lo paise lo.

Nasir- Aap dekhiye pehle allah pak ki kasam khaiye, aap kuch kar to nahi rahe hain?

Reporter- Allah pak ki kasam.

Nasir- Sir pe haath rakho mere..chota bhai hoon.

Reporter- Haan lo paise lo.

[Nasir grows increasingly suspicious of the reporter’s intentions, perceiving his continuous questioning as dilly-dallying tactics to buy time. His wariness reflects the inherent distrust within illegal trades. It is held that in such environments, reassurance and personal connection play pivotal roles in securing transactions.]

We left Nasir with the Chinese Manjha after paying him Rs 700 for the Manjha he had brought. We didn’t take the Chinese Manjha from him because it is banned in India.

After Nasir, we met Rajesh Singh in Delhi. In a revealing conversation with Rajesh Singh, a Kolkata native, the reporter explores the availability of banned Chinese Manjha in the city. Rajesh, candidly, explains how shopkeepers adapt to police scrutiny, often concealing their stock but readily supplying it when the coast is clear, reflecting the underground market’s resilience.

Reporter- Ab bata Chinese manjha.. ki kahan kahan mil raha hai Kolkata mein..?

Rajesh- Chinese manjha Kolkata mein har jagah milta hai, ban hai par police aata hai to sab chupa deta hai.

[Rajesh’s insights illustrate the widespread availability of banned Chinese Manjha despite police enforcement. It emerges that in Kolkata’s markets, the dance between law enforcement and illicit supply is a daily reality for traders.]

In this exchange, Rajesh Singh provides a candid glimpse into Kolkata’s underground market for banned Chinese Manjha. He describes how shopkeepers cleverly conceal their stock from police patrols, creating a temporary display of Cotton Manjha before resuming sales of the illicit product when the coast is clear.

Reporter- kaun kaun sa market hai..?

Rajesh- Kolkata poora hi market hai..kolkata mein aap kahin par bhi chota sa dukan le lo bada sa dukan le lo..jab gadi dekhta hai sab chupa jaata hai, dhaga wala saamne chalu ho jata hai, phir jab gadi gaya phir Chinese wala shuru ho jaata hai..

[Rajesh’s account reveals that Kolkata’s markets thrive on this illicit trade. It emerges that resourcefulness and adaptability are key for traders operating in this shadowy economy.]

In this insightful conversation, Rajesh Singh sheds light on the specific areas in Kolkata where banned Chinese Manjha can be found. He named Titagarh and Bada Bazaar, the two markets of Kolkata where Chinese Manjha is available. He said in Bada Bazaar, Chinese Manjha is available round the clock.

Reporter- Kaun-kaun se elake hain Kolkata ke..jahan Chinese manjha milta hai..?

Rajesh- Wahan humko Chinese manjha ka naam nahi pata..wo log lekar aata hai rang birangi..

Reporter- Lekin elaka kaun kaun sa hai ?

Rajesh- Accha elaka ho gaya Teetagarh.

Reporter- Ye Kolkata mein hai ?

Rajesh- Haan Kolkata mein.

Reporter- South-east ya north-west..kaun si jagah.?

Rajesh- South mein.. sab jagah mein hai, hadh se aadha ek ghante ka raasta hai..sab kuch milega…Titagarh ho gaya , Vada bazaar ho gaya….Bada bazaar mein to 24 ghante milega.

Reporter- Chinese manjha ?

Rajesh- 24 ghanta.

[Rajesh’s claim emphasizes the widespread availability of Chinese Manjha throughout Kolkata. It is clear that despite its ban, the product remains conveniently accessible, with some markets operating around the clock, showcasing the resilience of underground trade.]

In this brief exchange, the reporter questions Rajesh about the source of the charkhi he had sent on whatsapp. Rajesh reveals that it was sourced from Titagarh, indicating his local knowledge of the area while sharing that he lives just 15 minutes away from the airport.

Reporter- Tu ne kahan se liya tha jo mujhe charkhi bheji thi ?

Rajesh- Titagarh. Local hai.

Reporter – Local hai matlab tu wahin rehta hai..?

Rajesh – Hum to airport side mein rehta..wo 15 min ka raasta hai..

[Rajesh’sresponse highlights the close proximity of his residence to the source of the charkhi. It shows that local connections play a significant role in facilitating access to banned products in the area.]

In this exchange, the reporter probes Rajesh about the feasibility of supplying Chinese Manjha to Delhi. Rajesh confidently assures him that he can manage the task, outlining a straightforward plan to transport the goods by road within a few days, demonstrating his readiness for the illicit trade.

Reporter- To agar Chinese manjhe ka tujhe theka de diya jaye Delhi supply karne ka to tu kar lega?

Rajesh- Kar lunga.

Reporter- Kaise karega?

Rajesh- Wahi same..XXXX by road 3-4 din mein ke ander maal.

[Rajesh’s affirmative response underscores his willingness to engage in the supply of banned products. It emerges that the logistics of illegal trade are often simplified, relying on familiar routes and time frames to ensure delivery.]

In this startling conversation, Rajesh reveals the underbelly of drug trafficking. When asked whether he will be able to supply Chinese Manjha to Delhi through courier, Rajesh, in order to reassure us, revealed that through his courier company, he had supplied banned drugs, Ganja [Marijuana] from Kolkata to Bangalore, that too 5-6 kg in quantity.

Rajesh- Hum log jaisa kya karte..Banglore hum bheje weed.

Reporter- Hain?..weed ..weed matlab charas?

Rajesh- Nahi …Ganja..wo bheja Banglore Kolkata se..XXXXX se.

Reporter- Courier se bheja?

Rajesh- Courier se bheja..kab bheja..wo mere is phone mein nahi hai us phone mein hai…1-2 mahina nahi 2-3 mahine pehle.

Rajesh (continues)- 5-5, 6-6 kg Ganjha bheja.

Reporter- 5-6 kg Ganjha bheja?

Rajesh- Haan aaram se le liya..

Reporter- Aapne XXXXX courier se Kolkata se Banglore bheja?

Rajesh -Haan..hum aapko slip bhi dikha denge..par hum log ko pata hai na kya likhna chahiye..kya checking hota hai kya naam likhna chahiye….ab jaise ye pyaz hai… hum is pyaz ko pack kiya aur isko koi medicine ka naam de diya..kagaz pe medicine likha diya gadi mein rakh diya aur wo nikal gaya.

[Rajesh’s candid admission showcases the audacity and ingenuity of those involved in illegal drug trade. It emerges how the unscrupulous elements do deceptive courier packaging for evading law enforcement in this perilous business.]

In this revealing conversation, Rajesh claims even illegal firearms and weaponry can be couriered! Rajesh’s claims underscore the alarming reality of illicit markets operating under the radar, further highlighting the challenges law enforcement faces in curbing such activities.

Reporter – Hatiyar wagera sab..revolver etc. ?

Rajesh- Haan chota samaan hoga nikal jayega.

Reporter- Revolver wagera nikal jayegi ?

Rajesh- Haan.

Reporter- Kaun kaun se item ?

Rajesh- Koi bhi item.

Reporter- Jo bhi ban illegal hain…saare. ?

Rajesh- Haan…wo hum bhijwa denge.

[Rajesh claimed that he could even supply arms and all illegal and banned items also through his courier company]

In the following exchange, Rajesh discusses the dangers associated with using Chinese Manjha, particularly its potential to cause serious injuries.He confessed that with his own eyes, he had seen people dying and getting injured by Chinese Manjha. But despite that, he is ready to supply the illegal product from Kolkata to Delhi.

Reporter- Bada khatarnak hota hai..us sey log bhi marr gaye hain…Chinese manjhe se..

Rajesh – Accident bhi hotey hain, jo helmet lekar chala raha hai, najdeek jiske nahi hota kaanch, uska yahan se lekar yahan tak katke nikal gaya..

Reporter – Gurden kat jati hai

Rajesh- Aankh ke saamne dekha hai maine ye sab..

[Rajesh’s vivid descriptions of accidents caused by Chinese Manjha reveal the tragic consequences of this seemingly innocuous pastime, underscoring the urgent need for creating awareness and enforcing regulation in kite flying practices.]

Now, Rajesh sheds light on the dark underbelly of the Chinese Manjha trade, alleging the local law enforcement’s role in its proliferation. “Have you ever been raided by Kolkata police for selling Chinese Manjha?” In response to this, Rajesh said the police take Rs 500 as bribe from the accused and release them!

Reporter- Kabhi pakde nahi gaye?..Police ne raid nahi ki Chinese manjhe ki ?

Rajesh- Pakadne ki kya…police to khud khata hai….by chance agar hota bhi hai to wo cell nahi hota bomb..wo bhi ban hai .

Reporter- Kaun sa cell..?

Rajesh- Cell ho gaya…rocket ek ho jata hai, charkhi warkhi, wo jo uper jakar phatta hai, wo sab banta hai.. wo kya hai…police ko pata hota hai ki ye yahan se sale hota hai, policewala khada rehta hai bahar..ke koi lekar nikle, hum usko pakde, wo kya karta hai 500 rupees le leta hai uska samaan le leta hai..phir usi ko jakar de aata hai charkhi wala ko, ab wo phir se bechta hai, yahi hai police sab mein rehta hai bhaiya..

[In this revealing conversation, Rajesh discusses the police’s complicity, highlighting how they turn a blind eye, perpetuating a cycle of illegal sales and corruption that endangers the community.]

After Rajesh Singh, Tehelka met Javed Khan (name changed), whose friend Shyam Kumar from Shahdara, Delhi, is ready to sell Chinese Manjha to us at the rate of Rs 500 per roll. But according to Javed, he will not deal directly with us, he will deal through him.

Tehelka’s investigation into the banned Chinese Manjha across Agra, Kolkata, and Delhi revealed a disturbing reality: the ban has had little to no effect. Suppliers blatantly defy the law, and continue to sell the dangerous product.

Aam Aadmi Party leader Rajendra Gandhi spearheaded a protest last year in Varanasi against the sale of Chinese Manjha, highlighting the growing public concern. Both the Delhi and Allahabad High Courts have issued orders in the past prohibiting its sale. Yet, despite these legal actions and community efforts, the sale of Chinese Manjha go on unabated, leading to tragic consequences as innocent lives continue to be lost. This ongoing crisis underscores the urgent need for stricter enforcement and greater public awareness to protect citizens from this perilous threat.

To effectively address the ongoing issue of banned Chinese Manjha, the government must take decisive action. This includes enforcing stricter regulations and penalties for suppliers defying the ban. Regular inspections and monitoring of kite string sales in markets should be conducted. Additionally, public awareness campaigns highlighting the dangers of using Chinese Manjha could help educate consumers and discourage its use, and safeguard lives.