by Charanjit Ahuja

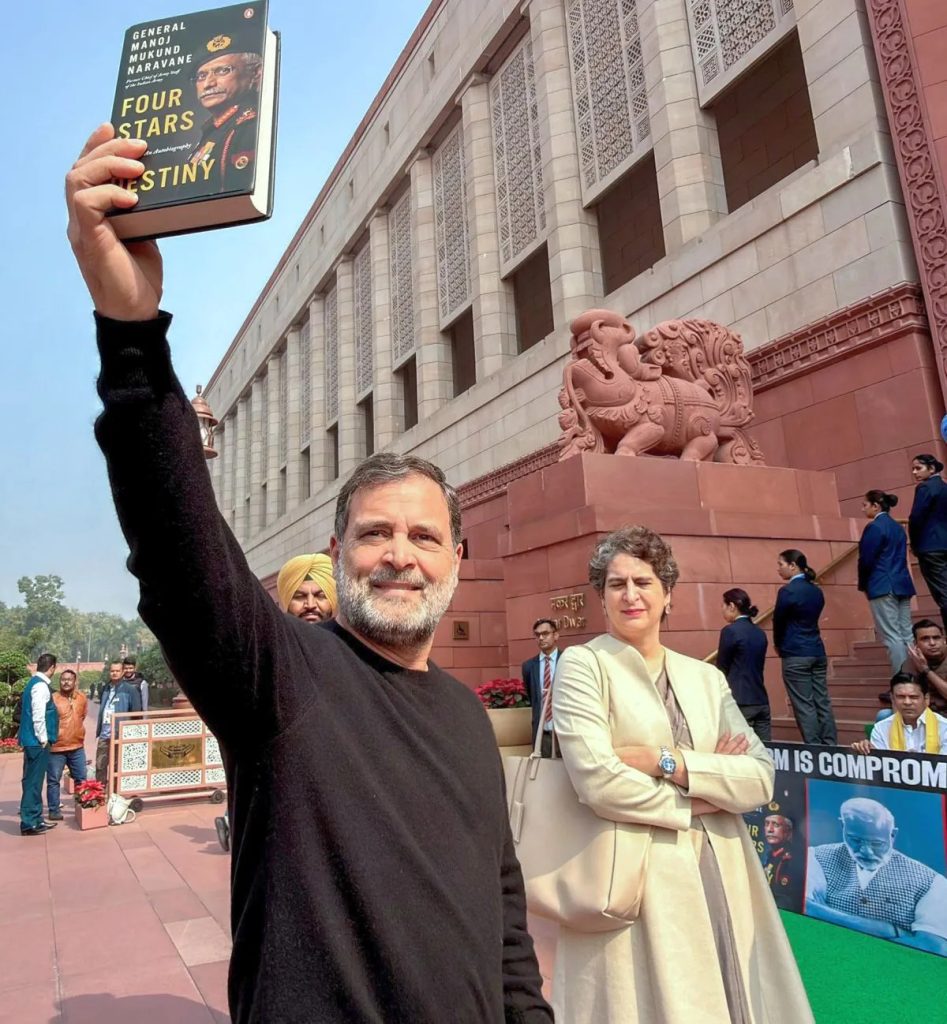

A book that is yet to be formally published triggered a full-blown confrontation in Parliament, raising questions that go well beyond its contents. When Leader of the Opposition Rahul Gandhi cited Four Stars of Destiny, a memoir attributed to former Army chief General Manoj Naravane, during a discussion on the 2017 Doklam standoff, the Lok Sabha descended into disorder.

The immediate controversy centred on Gandhi’s claim that the book refers to Chinese military assets, including tanks, entering Indian territory during the Doklam crisis — a claim strongly disputed by the government. But beneath the uproar lies a deeper constitutional issue: how far does parliamentary privilege extend when Members of Parliament rely on material the government considers “unpublished” or “unverified”?

While speaking on India-China relations, Rahul Gandhi invoked the former Army chief’s memoir to argue that Parliament had not been told the full truth about Doklam. According to him, the book suggests that Chinese forces crossed into Indian territory — contradicting the government’s long-standing assertion that there was no intrusion.

For the Opposition, the citation was intended to establish that concerns about Chinese aggression were not merely political claims but were echoed by a former top military commander. Gandhi sought to place this on record as part of a broader argument that the government consistently downplays Chinese actions along the Line of Actual Control.

Before he could elaborate, senior ministers objected, leading to repeated disruptions and the eventual disallowing of the reference. The government objected on multiple grounds. It questioned whether Four Stars of Destiny had been officially published or released for public scrutiny. Ministers argued that Parliament could not rely on selective excerpts from an unpublished manuscript, especially on a matter involving national security.

They also rejected the interpretation attributed to the former Army chief, maintaining that no official military assessment supports the claim that Chinese tanks entered Indian territory during Doklam crisis. From the government’s perspective, allowing such references would set a dangerous precedent—one in which unverified personal recollections could be presented as authoritative evidence in Parliament.

Privilege and the Constitution

This is where the episode acquires constitutional significance.

Under Articles 105 and 194 of the Constitution, Members of Parliament enjoy wide-ranging privileges, including freedom of speech within the House. These privileges exist to ensure that legislators can speak freely, without fear of legal consequences, to hold the executive accountable.

Crucially, parliamentary privilege is broader than the rules of evidence that apply in courts. MPs routinely cite newspaper reports, expert opinions, leaked documents, and books — none of which are “verified” in a judicial sense. The House itself is traditionally the forum where claims are contested politically, not pre-filtered administratively.

From this standpoint, the Opposition argues that it is Parliament’s role to debate and challenge claims, not to silence them on grounds of publication status. If a reference is inaccurate or misleading, the government has both the opportunity and the obligation to rebut it on the floor of the House.

At the same time, parliamentary privilege is not absolute. The Speaker has the authority to regulate proceedings and disallow references that violate rules, mislead the House, or compromise national security.

The ruling to disallow Gandhi’s reference reflects an expansive reading of this authority — one that prioritises procedural certainty and executive assurance over open contestation.

Critics argue that such interventions risk narrowing the scope of parliamentary debate, especially when they align closely with the government’s discomfort. Supporters counter that allowing references to unpublished defence-related material could blur the line between scrutiny and speculation.

Doklam: Controlling the narrative

The sensitivity of the Doklam episode amplifies the stakes. The 2017 standoff is frequently cited by the government as an example of diplomatic and military firmness. Any suggestion that Chinese forces crossed into Indian territory — particularly with armoured units — directly challenges that narrative.

Coming from a former Army chief, even indirectly, such a claim carries symbolic weight. It is precisely this weight that explains the government’s resistance to allowing the reference to stand unchallenged.

Yet, constitutional scholars point out that narrative control cannot be the basis for limiting parliamentary speech. Democracies function on the premise that uncomfortable claims are addressed through debate, not exclusion.

Military memoirs occupy an uneasy space in public discourse. They are neither official documents nor casual commentary. While they reflect personal recollections, they also shape public understanding of history.

The government is correct in noting that a memoir does not automatically represent the institutional position of the armed forces. But the Opposition is equally correct in arguing that such accounts can be legitimate triggers for parliamentary questioning. The Doklam standoff of 2017, involving Indian and Chinese troops near the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction, remains one of the most sensitive episodes in recent India-China relations. The government has consistently described the disengagement as a diplomatic success that restored the status quo without territorial loss.

Any suggestion that Chinese forces crossed into Indian territory, particularly with armoured units, directly challenges that narrative. Coming from a former Army chief — even if indirectly and through an unpublished account — such a claim carries political weight far beyond an ordinary critique.

For the Opposition, the book offered an opportunity to question the government’s transparency on China. For the government, allowing such claims to stand uncontested in Parliament risked legitimising what it views as a misleading or incomplete reading of events.

The Constitution does not require MPs to rely only on government-certified material to perform their oversight role. Rahul Gandhi was stopped not simply because the book was “unpublished,” but because allowing the reference would have forced a substantive debate on a sensitive issue the government prefers to treat as settled. Rahul Gandhi’s attempt to cite Four Stars of Destiny was less about the book itself and more about what it symbolised: a challenge to the government’s monopoly over the narrative on China.

He was stopped not only because the book was described as unpublished, but because its alleged contents strike at the core of a politically and strategically sensitive issue. Allowing the claim to be aired would have forced the government into a detailed rebuttal — or a clarification — on the floor of Parliament.

By disallowing the reference, the Speaker’s ruling effectively drew a line between what can be debated as fact and what remains, for now, in the realm of personal recollection. The government’s position emphasises institutional authority and official records. The Opposition’s stance stresses Parliament’s right to question executive claims, especially on matters as consequential as territorial integrity.

The decision highlights a growing tension in Parliament: between maintaining order and preserving the House as a space for rigorous, even uncomfortable, scrutiny.

The Bottom Line

The uproar over Four Stars of Destiny is not really about a memoir. It is about the shrinking space for contested truths in Parliament.

Parliamentary privilege exists precisely to allow elected representatives to raise questions that may embarrass the executive. When procedural objections are used to prevent such questioning altogether, the balance tilts away from accountability.

Whether or not the claims attributed to the book withstand scrutiny is a separate matter. The constitutional issue is simpler — and more troubling: should Parliament be a place where claims are debated, or filtered before they can be spoken?That question, more than the book itself, is what truly disrupted the House.