From the street corner to the shrine, how beggars are fast adapting to QR codes and digital transfers to receive alms. A report by Tehelka SIT

In a strange twist to the government’s push for a “Digital India,” the country’s beggars too have decided to go cashless. Some now sport QR code placards around their necks or carry a tablet, offering passers-by the option to pay alms with a scan. Those without personal digital access rely on trusted neighbourhood shopkeepers—sharing their QR codes or UPI IDs—who accept the donations on their behalf and return the equivalent in cash.

What was once an act rooted in folded hands and spare coins has now entered the age of e-wallets and UPI transfers, where the language of alms is increasingly spoken in digital code.

It may sound unbelievable to some, but across India, beggars have embraced digital payments, reshaping the very act of begging in this new age. Take Raju Singh from Delhi. “I accept digital payments, and it’s enough to get the work done and fill my stomach,” he said. A self-professed follower of former Bihar chief minister Lalu Prasad Yadav, Raju also makes it a point never to miss Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Mann Ki Baat radio address.

Raju explained that he could not find any other means of livelihood. Many times, people refused him alms, citing the absence of small change. Travellers in particular would argue that in the era of e-wallets and pay apps, there was no longer any need to carry cash. That pushed Raju to open a bank account and get an e-wallet. While most people still hand him cash, some do transfer money digitally. To open the account, the bank insisted on his Aadhaar and PAN, so he even went ahead and had a PAN card made to set the process rolling. Today, Raju begs digitally across Delhi.

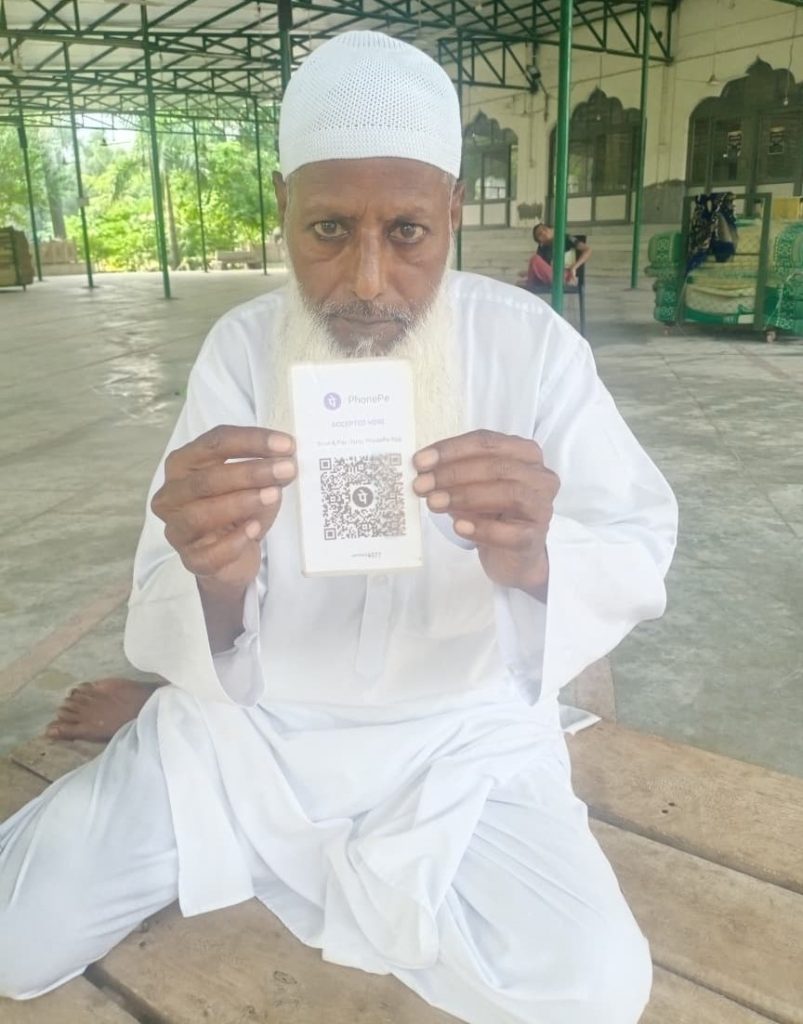

“Today at the Friday prayers in the Noida mosque, I got 4–5,000 rupees as alms in cash. Since I also have a scanner, I received some money through digital payment too. How much exactly? That I’ll have to check,” said Mohammad Akhtar, a beggar at the Noida mosque where Muslims gather in large numbers every Friday for the special namaaz.

“I am presently living in Badarpur, Delhi. But someone advised me to visit the Noida mosque on Fridays, saying the alms would be better. So I came here. To get the scanner, I had to open a bank account,” Akhtar told Tehelka.

“Today when I left my Noida home for begging, I told my local grocery shop owner I would use his Paytm UPI ID for digital transfers of alms. Because today is the digital world and most people prefer paying that way,” said Afsana, another beggar.

“Today I am begging with my two minor children, Neha and Bilal. I want my daughter Neha to get married, for which I am collecting money. My husband Nizam works in Gorakhpur as a domestic help, earning 4–5,000 rupees a month,” Afsana added.

“I have been living in this graveyard for the last 25 years, begging. People come and give alms to me. Every Friday I get around 400–500 rupees, and on Eid about 1,500. Now I have opened a small tea stall, but people who have long given me alms still donate—either in cash or by scanning. Today I even have a scanner, and those who want to give digitally, use it,” said Rehana Khatoon, another beggar.

“This scanner belongs to my local shopkeeper, Intezaar. I collect money through it and then buy rations from his shop. I live in Ghaziabad and come to Noida and Shaheen Bagh to beg. On Fridays alone, I manage to collect 300–400 rupees,” Rehana added.

“Please make the digital payment to this shopkeeper—we will get the money from him. But don’t give only to me, give to all the beggars sitting in the dargah campus. Otherwise I will face their wrath,” said Gopichand, a beggar at Matkapeer Dargah, near Bharat Mandapam in New Delhi.

“You can see the attitude of these beggars—they earn 400–500 rupees a day. Don’t give them money; they misuse it on illegal substances like drugs. Instead, arrange tea or biscuits for them with that money. By the way, I accept digital payments on their behalf and then distribute cash to them,” said Irfan, a shopkeeper at Matkapeer Dargah.

“Those who want to give us alms digitally—we take them to the chaiwala. They pay him online and we get the money in cash from him. I’ve been begging at Matkapeer Dargah for the last 20 years,” said Geeta, another beggar there.

“Yes, I accept money from people who want to give digitally to beggars, and then return it to the beggars in cash. I am from West Bengal and have been running my tea stall at Matkapeer Dargah for 20 years,” said Lab Karmakar, a shopkeeper.

Begging is illegal in those Indian states that have adopted anti-begging laws, most of which are based on the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959. These laws criminalise the act of soliciting alms and allow authorities to detain offenders in designated institutions. However, there is no single national law against begging—each state and Union territory has its own legislation. Critics argue that these laws are outdated, punish the vulnerable, and fail to address the root causes of poverty.

In 2018, the Delhi High Court struck down key sections of the Bombay Act, decriminalising begging in the capital. The court held that treating begging as an offence was unconstitutional and a violation of fundamental rights. Still, it remains a crime under Section 363A of the Indian Penal Code to kidnap, maim, or use a child for begging.

In Uttar Pradesh, however, begging continues to be illegal under the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Beggary Act, 1975, which makes it a punishable offence and allows for arrest and court proceedings. Section 76 of the Juvenile Justice (Care & Protection of Children) Act, 2015 also makes employing a child for begging an offence, punishable with up to five years’ imprisonment or a fine of one lakh rupees.

There are no recent official figures on India’s beggar population. The last data presented in Parliament was on December 14, 2021, based on the 2011 Census. According to that, India had over 4.13 lakh beggars—2.21 lakh men and 1.92 lakh women. More than 61,000 were below the age of 19. West Bengal topped the list with 81,244 beggars, followed by Uttar Pradesh (65,835), Andhra Pradesh (30,218), and Bihar (29,723).

The reason for revisiting the subject today is the surprising shift to digital payments among beggars. Reports of QR codes being used to collect alms have surfaced from many parts of the country, sparking curiosity. A recent viral video even showed a man on the roadside calling himself a “VIP beggar,” refusing to accept anything less than 200 rupees. Crowds gathered to see him, but no one donated because he would not accept anything less than Rs 200!

To probe deeper into this phenomenon of “digital begging,” Tehelka conducted an investigation in Noida and Delhi. The first encounter was with Afsana, who was begging along with her two minor children—daughter Neha and son Bilal—outside a mosque in Noida. She said she was seeking alms to get her daughter married. By doing so, Afsana committed three offences: using minors for begging, begging in Uttar Pradesh where it is illegal, and intending to marry off a child.

In this exchange, Afsana openly admits that she is seeking alms on the pretext of her minor daughter’s marriage. The reporter reminds her that the girl is only 15, far too young for marriage, and urges her to focus on education instead. Afsana, however, insists that poverty leaves her with little choice, falling back on the argument of survival. The dialogue exposes both her desperation and her resignation.

Reporter- To aap shaadi ke liye paise mang rahi ho?

Afsana- Haan bhai-jaan, kuch madad ho jaata to?

Reporter- Neha to abhi bahut choti hai…kitni umar hai iski?

Afsana- 15 saal.

Reporter- Itni kam umar mein shaadi….ye to gunah hai.

Afsana- Arey kuch nahi to jugad to ho jayega.. shadi to 2-3 saal baad karenge. Ab aaye hain to kuch jugad ho jaaye…rashan ka ho jayega?

Reporter- Kya naam bataya aapne?

Afsana- Afsana.

Reporter- Ladki bahut choti hai.. abhi shaadi ka mat socho; padhai karwao.

Afsana- Bhai jaan kya karen…gareeb aadmi hain, dar-dar ghoomna bhi to accha nahi lagta.

[When our reporter tries to dissuade Afsana from planning her minor daughter’s marriage, she insists that poverty leaves her with little choice, falling back on survival as her only argument. The exchange reveals both her desperation and resignation.]

We asked Afsana whether she had a QR code through which we could transfer money to her. She replied that she could share the Paytm UPI ID of her local grocery shop owner in Noida, to whose number digital alms could be sent. Afsana said she is originally from Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, and has been living in Noida for the last 4–5 years with her two minor children. She added that her husband works as a domestic helper.

Reporter-Scanner hai aapke pass?

Afsana- Scanner to nahi hai…number hai…ladki jaati hai ration wale ke dukaan par.. ration le lega bhai.. bacche bhooke hai bahut pareshan hain.

Reporter- Aapke pass scanner hai to de do?

Afsana -Scanner nahi, number hai…number par Paytm kar do to ho jayega..Paytm ka number hai bhai jaan, pareshan hoon bahut..Afsana naam hai mera, Gorakhpur ki rehne wali hoon.

Reporter- Yahan Noida mein kaise?

Afsana- Wahan rehte hain Noida 37 mein bhai jaan. Kya karen…kuch bacche log ko khane ke liye nahi hai.

Reporter- Shadi to ho gayi aapki?

Afsana- Haan ye beti hai meri.

Reporter- Shauhar kya kartey hain?

Afsana- Wo jhadu pocha ka kaam kartey hain….usmein poora nahi hota hai.. ab ladki ke liye bhi to jodna hai.

Reporter- Kitne bacche hain appke?

Afsana- Do bacchey hain.

Reporter- Kya naam hai bacchon ka aapke?

Afsana-Ladka-Bilal, ladki-Neha.

Reporter- Ye to Hindu naam hai! School nahi jaatey aap log?

Bilal- Jaata hoon.

Reporter- Kaun si class mein?

Afsana- Madarse mein jata hai.

Reporter- Madarsa kahan hai yahan?

Afsana- Noida mein.

Reporter- Kahan rehti hain aap?

Afsana- Sombazar mein, sector nahi pata… Sombazar ke peeche jhuggi hai hamara.

Reporter- Kitne time se reh rahi hain?

Afsana- 4-5 saal se reh rahe hain.

Reporter- Aap kaam nahi karti?

Afsana- Yahan kaam karne ke liye pehchaan patra mangtey hain…lekin hamare pass nahi hai.

Reporter- To aap shadi ke liye paise mang rahi ho?

Afsana- Haan, bhai jaan, kuch madad ho jaata to.

Reporter- To shauhar to aapke 4-5 hazar kama rahe hain?

Afsana- Haan. Kama rahe hain gaon mein.

Reporter- Gaon mein hain.. yahan nahi?

Afsana- Haan.

[Here, the reporter presses Afsana on her reasons for seeking alms, even questioning her daughter’s schooling and her child’s Hindu-sounding name. Afsana insists her struggles leave her with no other choice. The dialogue underlines how poverty, lack of identity papers, and low income push families into dependency.]

When asked whether the shopkeeper, on whose QR code Afsana was requesting us to send money, could be trusted to pass it on to her, she replied that he was indeed a reliable man. A Muslim named Saeed, he provides her with rations once money is sent to his number. Afsana also mentioned that on the day she met the Tehelka reporter at a mosque in Noida during Friday prayers, it was raining heavily and consequently she received no alms.

Reporter- Agar aapke pass scanner hota to main madad kar deta.

Afsana- Number hai, ration waley ka, thoda bahut ration dila dogey to chaley jayenge.

Reporter- Dekho behan meri, mein dukandaar ko kar doon, lekin agar won na de aapko?

Afsana- Dega. Vishwas hai hamko…wo bhi koi Hindu nahi, bhai jaan.. Musalmaan hai.

Reporter- Kya naam hai dukandaar ka?

Afsana- Mohd. Saeed.

Reporter- To aap paise waisey hi mangawatey rehtey ho wahan?

Afsana- Nahi –nahi.

Reporter- Phir?

Afsana- Hum unko bol detey hain ke koi aapko paytm kar deta hai to humko rashan de do, jitna karengey utne ka humko tel, chawal, dal deta hai. To aaj aayi, masjid mein paani barasney laga.., kuch nahi mila.

Reporter- Jume ki namaaz mein aayi thi?

Afsana- Haan…lekin kuch nahi mila.

[In the above exchange, Afsana reveals she depends on her local grocer’s Paytm account to receive digital alms. She stresses her trust in him, pointing out that he belongs to her own community. She explains how donations made to his number are converted into rations—oil, rice, and pulses—for her family.]

Afsana then gave us the shopkeeper’s number, and asked that money be transferred to him. She explained that in today’s digital world, everyone uses Paytm, so she had already informed the shopkeeper that while seeking alms she would share his number with donors for digital transfers.

Afsana- Hum usko bolkar aaye hain na bhaijaan aise hum ja rahe hain, koi dega ya nahi dega, paytm ka aajkal zyada system hai. To wo bol raha tha aap number de dena hum ration de denge. Ek daana bhi nahi hai khaney ko…5 -6 din se barish ho raha hai.

Reporter- To aap usko bolkar aayi ho mein ja rahi hoon mangne?

Afsana- Nahi mein kalam-walam bechti hoon, maine socha isey bech lungi koi banda mil jaye.. mujhe rashan washan de de. Mainey bola tha ek bhai ko…wo bola yahan aapka fariyad kar lo. Idhar, bhai jaan aap mil gaye.

Reporter- Agar usne nahi diya ration aapko? Jhoot bol diya nahi mile paise?

Afsana- Nahi bhai jaan, aise nahi hai wo.

Reporter- Kya number hai?

Neha- 98715XXXXX

Reporter- Is number par paytm karna hai, aapka naam Afsana hai?

Afsana- Haan, Neha ki mummy.

[In this exchange, Afsana speaks of her struggle to arrange food for her family, saying the local shopkeeper had assured her of ration if someone transferred money to his number. She adds that heavy rains had left her without grain for days. The account lays bare the extent of Afsana’s hardships—five to six days without food is no small trial.]

After a week, on Friday, Afsana was again seen at the same mosque in Noida, this time with only her minor son, Bilal. She was caught on camera begging, with her son holding a scanner in his hand. Afsana told the Tehelka reporter that since people no longer trust the shopkeeper’s Paytm number, she had brought the shopkeeper’s scanner with her for begging.

When confronted that thrusting her two minor children for begging is a crime, Afsana replied that she is poor, helpless, and needs money to survive. She also admitted that she receives 5 kg of free food grains every month under the government’s ration scheme, yet continues to beg.

When her attention was drawn to the fact that begging is itself a crime in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, she gave no reply. On being contacted, Afsana’s local shopkeeper Saeed—whose phone number and scanner she uses—confessed that he is digitally receiving the alms money on her behalf. Afsana explained that since she does not own a phone, she cannot have her own QR code.

Meanwhile, in the same mosque of Noida, on Friday, Tehelka’s correspondent met another beggar, Mohammad Akhtar, holding a scanner in his hand while seeking alms. He admitted that he had collected Rs 3-4K in cash and the rest digitally, through digital scans linked to his son’s account, on the same day. Akhtar, a resident of Badarpur in Delhi, had travelled to Noida and engaged in begging, which is illegal in Uttar Pradesh. He said that after opening a bank account, he received the scanner, which he now uses for begging.

Reporter- To aap Badarpur se paisa mangne ke liye yahan aatey ho Noida?

Akhtar- Hum kabhi nahi aaye… bata to rahe hain ye bhai ghoomtey rehtey hain…kapde ka kaam kartey hain, dari bechtey hain. To unhone batai thi ye masjid, ki wahan chale jao, Allah tumhara kara dega kuch na kuch.

Reporter- Yahan pehli baar aaye ho?

Akhtar- Haan, pehli baar.

Reporter- Kitna paisa mil gaya?

Akhtar-3-4 hazar mil gaye.

Reporter- Scanner par liye honge aapne?

Akhtar- Kuch scanner par pahuch gaye…aur baki ye hain.

Reporter- Ye sab aaj hi ka collection hai?

Akhtar- Haan ye abhi ka hai.

Reporter- 3-4 hazar ho gaye?

Reporter (continues)- Scanner par kitne aa gaye?

Akhtar- Ab poochengey jakar….ismein awaz hi nahi aa rahi ye mobile mein.. iska speaker kharab ho gaya.

Reporter- Aapka smartphone hai na?

Akhtar- Haan ye hai…iska speaker kharab ho gaya hai.

Reporter- Haan to ye scanner hai aapka.. isi se paise mang rahe hain aap?

Akhtar- Ye hamare bete ka scanner hai…khaata hamne khulwaya tha… ismein se nikal kar de denge.

Reporter- Scanner se kitna mil gaya aaj aapko?

Akhtar-Ismein to poochna padega kitne aaye aaj, dekha nahi… jo kuch Allah ne bhej diye honge.

[In this exchange, Akhtar explains how he came to Noida’s mosque for the first time on someone’s advice, hoping for help. We learn that alms are now tracked through scanners and smartphones. What emerges here is how even begging has been reshaped by digital tools.]

Mohammad Akhtar, a resident of Jalaun, Uttar Pradesh, came to Delhi and then to Noida for begging. He said that he was collecting money for his nephew’s surgery through begging.

Now, Tehelka met another beggar, Rehana Khatoon, originally from Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, and now living in Noida. She admitted that she has been begging in the graveyard for the last 25 years—again, a crime under Uttar Pradesh law. Rehana said she receives about Rs 1,500 on Eid through begging, and around Rs 400–500 every Friday. She has also opened a small tea stall at the gate of the mosque, which shares the premises with the graveyard. According to her, she now uses a scanner to receive alms, in addition to cash, from her regular acquaintances who continue to support her with alms despite her stall.

Reporter- Ab paise nahi maang rahi aap?

Rehana- Koi de gaya apni raji khushi se to alag baat hai, to le leti hoon.

Reporter- Nahi ye aapne bahut accha kaam kiya….scanner bhi le liya aapne.

Rehana- Ye laga diya company walon ne free mein… paisa nahi liye. Wo laga rahe they tab mein rone lagi ke mere pass kuch bhi nahi hai.

Reporter- Arey to aap cash le leti…scanner thodi tha pehle.

Rehana- Nahi ab scanner laga liya…ladko ka kya bharosa de na dein.

Reporter- Aap to ander hi rehti hain na masjid mein?

Rehana- Haan.

Reporter- Pehle bhi to accha collection ho jata tha aapka jume ke jume, Eid ke Eid.. kitna kama leti thi aap?

Rehana- Eid par to mil jata tha kareeb 1500 aur jume par 400-500 rupaiye, koi jaaney wala 500 alag se de jata tha.

Reporter- Yahan kab se reh rahi hain aap…kabristan mein?

Rehana- 25 saal ho gaye.

Reporter- Ab koi aapko paise dene aata hai to kaise leti ho.. scanner se?

Rehana- Jisko jaise dena hota hai…scanner se ya cash…log aise hain kehtey hain aap bethi raho aunty…manga kisi se nahi…na pehle na ab..log khushi se de jaate hai.

Reporter- Abhi bhi koi dena chahe to de jaaye?

Rehana- De jaaye…Allah deta hai beta.

Reporter- Abhi de jate hain log…jo pehle de jaatey they?

Rehana- Haan, abhi ek banda 100 de gaya…aur ek 20 rupiya.

[In this exchange Rehana explains how she began using a scanner, fitted free by a company, to receive alms—though she still accepts cash. She says donations come willingly and that Eid and Fridays bring better collections. Rehana treats occasional small gifts as blessings.]

During the investigation, Tehelka met two more beggars—Rehana from Ghaziabad and Reshma from Faizabad—both hailing from Uttar Pradesh. The two were found begging in Noida, which, as mentioned earlier, is a criminal offence since begging is illegal in Uttar Pradesh.

Rehana was carrying a placard with an appeal for alms along with a scanner for receiving donations. People were seen donating money to her through the scanner. She told Tehelka that she collects around Rs 300–400 on Fridays, and revealed that the scanner she uses belongs to her local shopkeeper, Intezaar.

Reshma, who lives in Sombazaar in Noida, provided the phone number of her local shopkeeper, Shahzaad, through which she receives digital transfers of alms. However, when contacted, Shahzaad’s phone was found to be switched off.

Tehelka’s digital beggars story now moves from Noida to Delhi, where we met a group of beggars at Matkapeer Dargah near Bharat Mandapam in New Delhi. We first spoke to Nasreen, who has been living at the Dargah and begging for the last 35 years. She laments the meagre earnings of the day—barely sixty rupees—despite it being a Thursday, usually a better day. She blamed the lean day on rain-flooded streets that kept people away. Nasreen does not have any digital platform of her own to receive alms, so she directed us to transfer money digitally to a flower seller at the Dargah.

Nasreen- Scanner uske pass hai.. phool wale ke pass.. usmein daal dena.

Reporter- Aapke pass nahi hai?

Nasreen- Hamare pass nahi hai, wo baant detey hain.

Reporter- Aaj mila nahi kuch?

Nasreen- Nahi mila.

Reporter- Aaj to jumeraat hai?

Nasreen- Subah se sirf 60 rupees mile hain.

Reporter- Jume raat ko bhi 50-60?

Nasreen- Public bahar nahi aa rahi na.

Reporter- Kyun?

Nasreen- Jagah jagah pani bhara hua hai.

Reporter- Normal din mein kitni ho jati hai amdani?

Nasreen- Rs100…. zyada se zyada.

Reporter- Aap kab se ho dargah par?

Nasreen- 30-35 saal se.

[At the Dargah, Nasreen reveals how she depends on a flower seller’s scanner to receive digital alms, since she has none of her own. We learn how beggars adjust by relying on others’ digital tools, showing how technology intertwines with poverty in uneasy ways]

Gopichand, another beggar who arrived at Matkapeer Dargah just a few months ago from Mahoba, Uttar Pradesh, took us to a florist’s shop at the shrine. He asked us to transfer alms digitally to the shopkeeper for all the beggars at the Dargah, warning that if the money was sent only for him, the others would make his life miserable.

Reporter- Chalo- chalo scanner par karwao?

Reporter (continues)- Hame inko paise dene hain, lekin inke pass scanner hai nahi.

Gopichand- Gopichand ko akele thodi dene hain… sabko dene hai.

Reporter- Ye tumhare pass layen hain paytm ke liye.

Irfan- Haan mujhe kar do.

Gopichand- Mere ko akele mat dena…sab ko dena.. nahi to sab chadh jayenge mere uper.

[This exchange shows the fragile balance within the group of beggars. We learn how even alms are bound by rules of collective survival. It underlines how poverty often creates its own codes of fairness, driven more by fear than equity.]

Irfan, the florist to whom Gopichand directed us for the digital payment, told us that the beggars’ conduct was questionable. He advised us not to give them money, but instead to arrange tea for them. According to Irfan, these beggars earn between ₹300–400 a day.

Irfan- Bheekh mangne walon ka ye haal hai.

Reporter- Ye kitna kama letey hain ek din mein?

Irfan- Kama letey hain 300-400.

Irfan (continues)- Aap meri baat suno…paise ka to ye galat istemaal kartey hain, aap inhe chai pila do.

[Irfan paints a picture of how begging works on the ground. He discloses the average daily earnings, which are not insignificant. Yet, he is quick to allege that the money is often misused. Instead, he suggests offering them tea.]

After speaking with Irfan, we met Geeta, another beggar at the Dargah who has been living there for the past 20 years. Geeta told Tehelka that whenever someone wishes to give them alms digitally, they take the person to Lab Karmakar, a tea stall owner at the shrine. Lab receives the money digitally and then gives them cash in return.

Geeta- Aap chai wale ke pass scanner par kar do…dene wale detey hain….nahi dene wale nahi detey.

Reporter- Agar kisi ke pass cash na ho to wo kaise karega?

Geeta- Arey meri baat suno…ye Lab hai iske pass kar do.

Reporter- Matakapeer par kab se ho?

Geeta- Hame 20 saal ho gaye.

[This exchange reveals how beggars depend on intermediaries to bridge the digital divide as Geeta, a long-time resident at the shrine, explained how digital alms are managed through one Lab, the local tea seller. We learn that survival has forced them to create informal systems.]

We decided to meet Lab Karmakar, who digitally accepts money on behalf of the beggars and later relays the same to them in cash. Lab, originally from West Bengal, has been running his tea stall at Matkapeer Dargah for the last 20 years. He told Tehelka that many people who wish to donate alms digitally pay through him, and he, in turn, hands the money back to the beggars in cash.

Reporter- Jitney bhikari hain sab keh rahe hain: ‘lab bhai ko de do’.

Lab- Haan koi dena chahta hai…kuch log de jaate hain hum de detey hain…cash nahi hota na… matlab ye hai.

Reporter- Bhikariyon ki bhi dua le rahe ho aap.

Reporter (continues)- Yahan kitna time ho gaya aapko?

Lab – Yahan 20 saal ho gaye…

[This brief exchange shows how an informal network sustains the practice of begging in the digital age. Having run his stall at Matkapeer for the past twenty years, Lab has become a familiar part of the beggars’ ecosystem.]

Tehelka’s investigation into digital beggars exposed many realities. Those able to open bank accounts are using their own QR codes or phone numbers for the digital transfer of alms. Those who cannot, and therefore lack QR codes or numbers, have devised a unique alternative for donors wishing to give digitally in the absence of cash. They rely on scanners, phone numbers, or Paytm UPI IDs of local shopkeepers, who receive the alms and then hand over the amount in cash to beggars. Afsana was caught on camera using her two minor children for begging and seeking money to marry off her minor daughter—both criminal offences. Beggars filmed in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, are also violating the law, since begging is illegal in the state. This investigation reveals not just illegality, but also the disturbing normalisation of such practices in the name of survival.