Where are prison diaries and books of the day? Why don’t prisoners write, so that we know what’s taking place in there? Are prisoners of the day discouraged from offloading their everyday experiences?

What can be termed as a series of shockers are reports coming in right from this summer of 2022 of several jailed inmates, imprisoned in the jails of Uttar Pradesh, testing positive for HIV. And some of the HIV infected also testing positive for TB.

Focusing on the news reports published earlier in June, about 22 inmates in the Saharanpur jail tested positive for HIV, and 6 inmates in the Gonda jail. And in early September, 26 inmates of the district jail at Uttar Pradesh’s Barabanki tested positive for HIV. News reports stated that the tests were conducted by the health department during a three-phase HIV camp held at the jail from August 10 to September 1, and of the 26 people, two were undergoing anti-retroviral treatment at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Lucknow.

And now, in November, comes in news from Ghaziabad situated Dasna Jail – that out of 5,500 inmates 140 are HIV positive, and 35 of them also have TB. These are officially released figures, together with this disturbing fact – currently, around 5,500 inmates are lodged in Ghaziabad situated Dasna jail against a capacity of 1,706 inmates.

How does one react to this? Shocking, to say the least. The only positive here is that at least the State has admitted this alarming fact – that is, HIV infected prisoners are there, imprisoned in those jails. Mind you, in all probability they couldn’t have been infected when they were initially jailed, because it is mandatory to conduct medical tests before imprisonment.

Relevant queries do come up: How did they get HIV infected in the confines of these jails and prisons? Why weren’t medical tests conducted on the prisoners when the initial symptoms came up? What steps are undertaken for deadly infections, including the tuberculosis infections, not to further and infect many more of the jailed population? What steps are being implemented or undertaken to lessen the overcrowding aspect to jails? Is the concept of open- jails a better option; with prisoners able to breath fresh air and move about along a larger stretch? Above all, what is the State doing for the under-trials? Technically innocent, as yet to be proven guilty yet they sit languishing for years, if not for decades. Wasted lives with sheer nothingness holding out!

Where are prison diaries and books of the day? Why don’t prisoners write, so that we know what’s taking place in there? Are prisoners of the day discouraged from offloading their everyday experiences or inner most thoughts and emotions? Are the imprisoned men and women reduced to such levels of hopelessness that they don’t want to yield the pen or else try to key in, that is, if computers and laptops are even available in the prisons in these ‘developed’ times? Also, is there that basic freedom for the imprisoned to write fearlessly and freely and in that ongoing way, day after day, in that imprisoned state?

When one thinks of prisoners of today, it gets significant to mention that perhaps prison conditions were relatively, rather significantly better, in those years passed by.

I just re-read this book – ‘Prison Days’ (Speaking Tiger) by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, with a foreword by her daughter, Nayantara Sahgal. This prison diary was written by her in the early 1940s, and as one reads through what comes out is the ground reality of that historic phase when hundreds of the who’s who were imprisoned. And these included Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and members of his family.

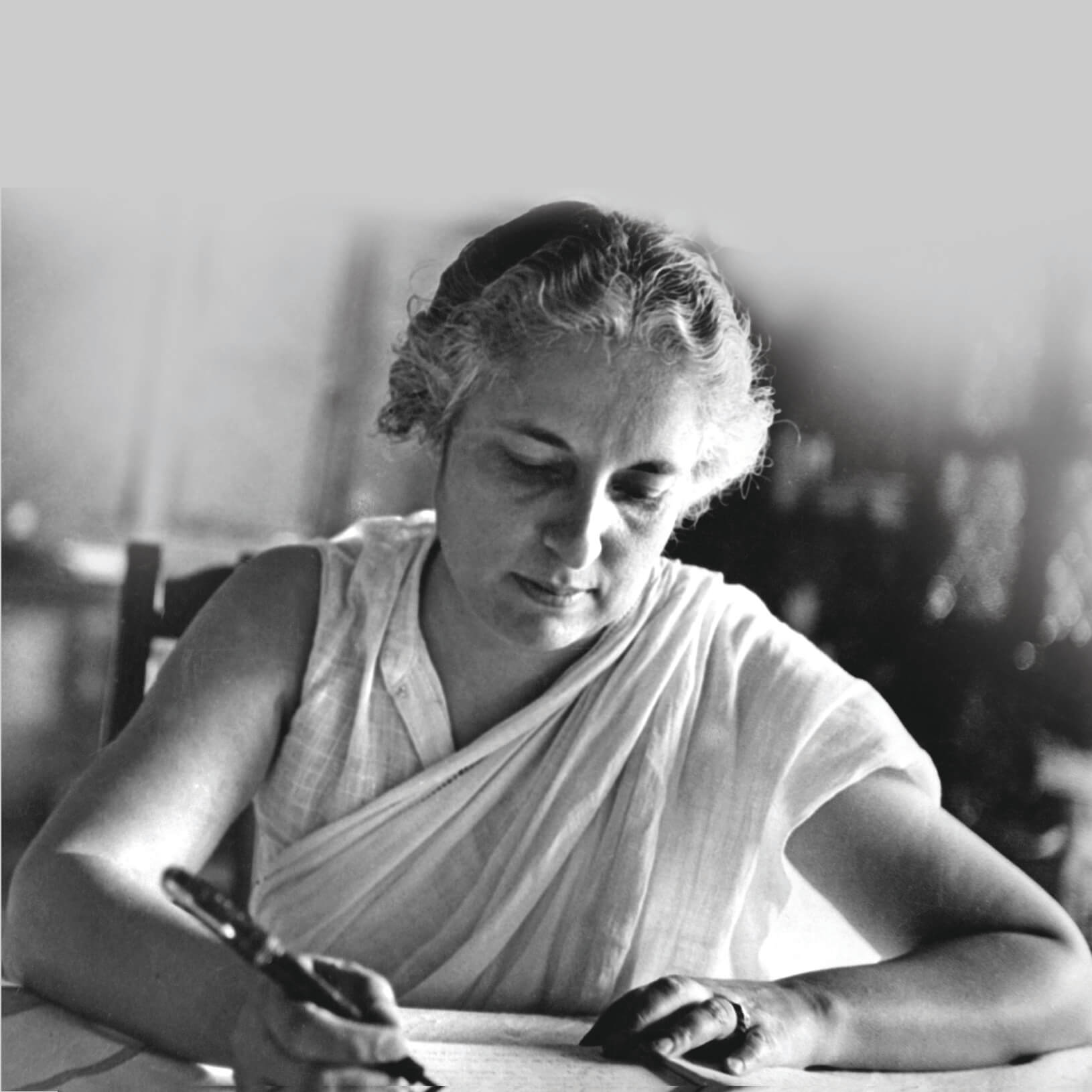

To quote Nayantara Sahgal from the foreword – “My mother, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, wrote this prison diary during her third and last imprisonment under British rule. It begins on 12 August 1942, six days before her forty-second birthday. World War11 was on, Allahabad, like the rest of the country was under military rule. Arrest and imprisonment took place without trial. Several lorries filled with armed policemen arrived that night at Anand Bhawan at 2 a.m. to arrest one lone, unarmed woman, who, along with her husband, Ranjit Sitaram Pandit, and her brother Jawaharlal Nehru, had committed her life to the non-violent fight to free India from British rule, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi…My father was already a prisoner in the Naini Central jail in Allahabad, where she was taken, and he would later be transferred to a jail in Bareilly, where he would fall mortally ill, and finally be released only to die. My uncle was imprisoned ‘somewhere in India’. It was not made public until much later that he and other leaders of the Indian National Congress were held in the Ahmednagar Fort. My older sister, Chandralekha, aged eighteen, and my cousin, Indira Gandhi, aged twenty-five, were arrested later and taken to Naini Jail.”

In this book, there is no mention of physical tortures inflicted on Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit but then as she writes in the preface, “This little diary does not attempt to record all the events which took place during my last term of imprisonment… the treatment given to me and to those shared the barrack with me was, according to the prison standards, very lenient – the reader must not imagine that others were equally well treated. When the truth about that unhappy period is made known many grim stories will come to light, but that time is still far away.”

After one has read through this slim book, one wonders where are the books written by prisoners of the day.

Lily Swarn Saba’s book of ghazals

Chandigarh-based poet Lily Swarn Saba’s book of ghazals –Yeh Na Thi Hamari Qismat- published in Urdu and Hindi ( yet to be translated in English) holds out on the sheer strength of her ghazals. Hitting, powerful and touching.

I’d first met Lily around 2019 at the South Asian literary-poetry meet organized by Ajeet Cour, in New Delhi, and what had immediately struck was Lily’s pair of eyes. There was a certain sadness spread out on her beautiful face, with the eyes relaying emotional strain or call it sadness. And over lunch as we got talking, she’d told me that her young son succumbed to cancer, leaving her and the family immensely pained and in deep sorrow.

In fact,she has dedicated her this book to her son – Gobind Shahbaaz Singh.

Though one is tempted to write one ghazal after another from her book as each ghazal holds out but space constraints come in way. Leaving you, with these lines from her book:

Dard hota nahin hai sabhi ke liyai

Yeh to tohfa bana hai kisi ke liyai…

(This pain is not for everyone, a present only for someone…)