The Gond and Mandana art forms which depict nature and wildlife can be tools for environmental awareness, writes Deepanwita Gita Niyogi

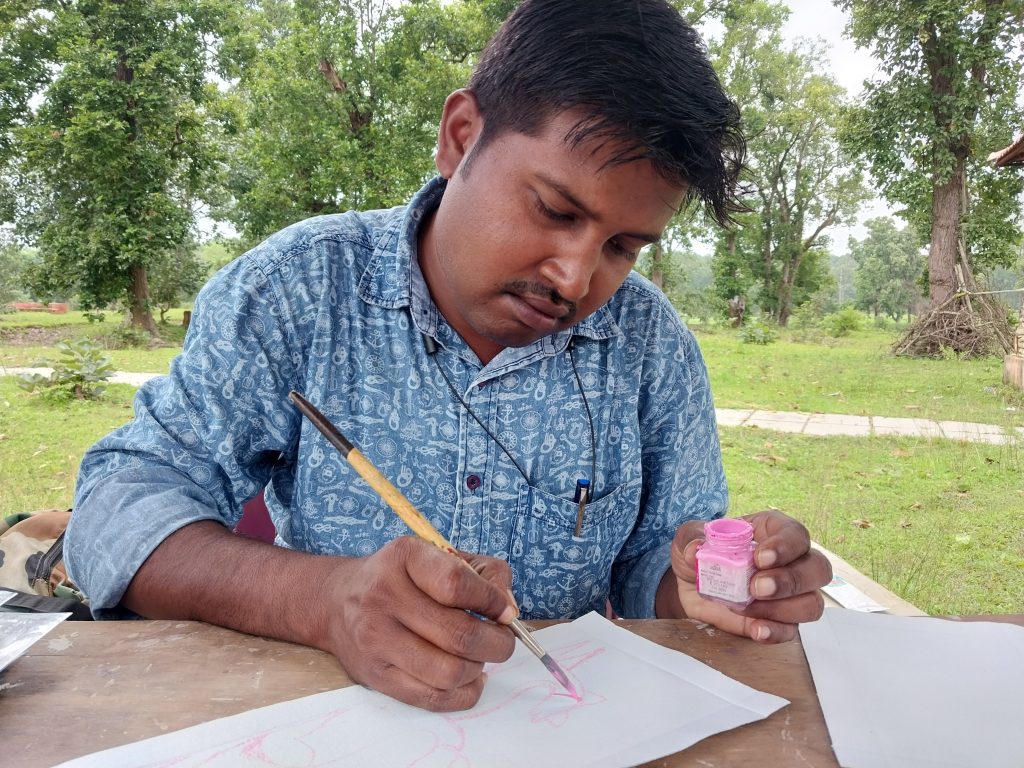

On a windy afternoon punctuated by intermittent rains, Gond tribal artist Rameshwar Dhurwey filled his painting of a barasingha or hard ground swamp deer with bright colours at the Baiga Haat of Kanha National Park where there are several stalls selling wooden items, clothes and jewellery.

The colour palette used in Gond art is vast, informed Dhurwey, who owns a shop at the place. “One can use almost any colour but the selection has to be proper for the effect to come alive on canvas and even on paper,” the artist based in Madhya Pradesh said.

Earlier, when acrylic colours were not in vogue and the paintings used to be made on mud walls in villages, artists used colours obtained from nature. For instance, neem and sem (Indian green bean) leaves were crushed to obtain shades of green to depict trees and animals.

According to Dhurwey, acrylic colours dry in eight hours, last long and are suitable for canvas and paper. “Though natural colours are not used that much these days, I still use the colour obtained from Palas flower on paper as well as canvas.”

Message of environmental conservation

The Gond art focuses on the depiction of animals like deer and tigers. The tree, often called the tree of life, is also an important feature of this art, added Dhurwey.

Through the paintings of birds, elephants, plants and flowers, the message of environmental conservation through the Gond art is clear.

The artist’s paintings, mostly executed on canvas with acrylic colours, are priced at Rs 3000 to Rs 6500. The minimum price is Rs 1000 for smaller paintings. “The Gond art is linked to nature and the tree of life is an important aspect of almost every image. Trees are important in tribal life. We worship the Saja tree a lot and pray to trees during important festivals,” said Dhurwey while first making an outline with a coloured chalk.

Dhurwey’s family members are also into Gond art. But at the insistence of his family, he completed his higher education. “Though my parents wanted me to do a regular job, I wanted to become an artist after completing my studies in Bhopal and Gwalior. I feel people should keep on doing creative things or else these will vanish forever.”

For medium-sized paintings, Dhurwey takes at least 10 hours as there are subtle designs and lines to be executed. The artist, who recently attended an exhibition in Chennai, admitted that there is a change coming in the art making it more modern.

“I feel that along with the tribal culture, the message of conservation has to be highlighted through Gond art. I try to capture various seasons apart from wildlife. One need not always fill up the entire canvas and white space can be left.”

Nature comes alive on walls

In the state of Rajasthan, just like the Gond art, the Mandana wall murals capture wildlife, especially the tiger. In the city of Sawai Madhopur famous for the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, images of tigers, peacocks, lotus, birds and even elephants can be seen etched in white against reddish walls.

In this tiger land, the traditional Mandana wall art is dedicated to nature. Once limited to the Meena Adivasi community, it has spread among others and undergone transformation with time. Modern influences have crept in with the disappearance of mud walls. In many villages, the colourful wedding art is now often seen in place of the traditional Mandana executed with white chalk on red to dark brown walls. Sometimes, a lighter shade of brown is also used.

The Gond and Mandana paintings reflect the primeval connection of human beings with nature and celebrate a sustainable lifestyle close to earth. But the construction of concrete houses is taking its toll on such age-old traditions in both the states. At an abandoned house in Bandha village of Sawai Madhopur, floral patterns made on mud floors were spotted. The family has shifted to a pucca house but the women return here around the time of Diwali to make the Mandana murals in white.

Divya Khandal, who runs social enterprise Dhonk, based in Ranthambore, said, “Once widespread in the entire region, the traditional Mandanaart is slowly vanishing.”

Art forms like the Gond art and Mandana murals point to the deep tradition of communities attached to forests for centuries. To sever their connection with nature in the name of development will not only kill art, but also impact tourism. Instead, such art forms can be promoted to convey the message of conservation at a critical time of deforestation and climate change.

For this very reason, Khandal does outreach programmes involving school students. “I organise competition on Mandana around Diwali and every year the theme is wildlife. In Ranthambore, there is a lot of tiger paintings as a result of the reserve. Involving students sends across the message of art and conservation at the same time.” This year too, Dhonk will try to reach out to 5,000 students in an effort to highlight the art. Apart from girls, even boys are also showing interest.