The demonstrations by farmers in different parts of India and in the national capital in the recent past and proposed protest on November 30 are indicative of an uprising. A series of protests by the communities under threat are a caveat by the food producers who face oppression in everyday life. Indian farmer with small landholding is in jeopardy. Having nothing to lose, he is now geared up to hit the streets more often and resort to massive agitations led by farmers’ organisations.

The demonstrations by farmers in different parts of India and in the national capital in the recent past and proposed protest on November 30 are indicative of an uprising. A series of protests by the communities under threat are a caveat by the food producers who face oppression in everyday life. Indian farmer with small landholding is in jeopardy. Having nothing to lose, he is now geared up to hit the streets more often and resort to massive agitations led by farmers’ organisations.

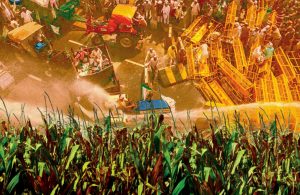

Thousands of farmers thronged the border of the country’s capital, New Delhi, on October 2 under the banner of Bhartiya Kisan Union to raise their demands. This massive protest was one of the latest after a similar protest staged at Parliament Street on September 5 by the three organisations- Centre for Indian Trade Unions, All India Kisan Sabha and All India Agriculture Workers’ Union, and Mumbai March by thousands of farmers of Maharashtra. All India Kisan Coordination Sangharsh Committee, an umbrella organisation of over 200 farmers’ union organised Kisan Mukti Sansad in November last year in the Parliament Street. The central issues were the denial of remunerative prices to farmers and piling farm debts pushing them into suicides. Two Bills — Farmers’ Freedom from Indebtedness Bill and Farmers’ right to guaranteed remunerative minimum support price for agriculture produce — were presented in the Kisan Mukti Sansad. This ended by declaring a plan for a

Thousands of farmers thronged the border of the country’s capital, New Delhi, on October 2 under the banner of Bhartiya Kisan Union to raise their demands. This massive protest was one of the latest after a similar protest staged at Parliament Street on September 5 by the three organisations- Centre for Indian Trade Unions, All India Kisan Sabha and All India Agriculture Workers’ Union, and Mumbai March by thousands of farmers of Maharashtra. All India Kisan Coordination Sangharsh Committee, an umbrella organisation of over 200 farmers’ union organised Kisan Mukti Sansad in November last year in the Parliament Street. The central issues were the denial of remunerative prices to farmers and piling farm debts pushing them into suicides. Two Bills — Farmers’ Freedom from Indebtedness Bill and Farmers’ right to guaranteed remunerative minimum support price for agriculture produce — were presented in the Kisan Mukti Sansad. This ended by declaring a plan for a

nation-wide campaign to spread public consciousness about the two bills.

The organisation has decided to organise another march-cum-rally on November 30 in New Delhi as their demand of a special session on private member bills in the Parliament on farmers’ issues has not been taken up by the Union Cabinet. Avik Saha, national convenor of Jai Kisan Andolan, told Tehelka, “We are trying to resolve the issue through dialogue and discussion but government is interested in monologue and advertisement. The crisis in the agriculture sector is a national crisis and why should the Parliament not discuss this? We need to break the myth that our farmers are a happy lot because a happy farmer does not come on roads to protest at the cost of his work.” He added that their movement is not a demand driven movement but a resolution driven movement and organised protests in a democracy are a rightful means to seek change in perceptions of people in the power corridors. The successive governments have failed to take up the cause of the farmers. The promises have been made to ameliorate the situation of farmers but the problems of farmers have been multiplying. Since the year 2006, farmers have come to believe that there is no solution to their hardships. The UPA government led by Dr Manmohan Singh constituted the National Commission for Farmers, ostensibly to bring about a comprehensive change in the deteriorating condition of the agriculturists. The recommendations of the Commission headed by Dr MS Swaminathan were not implemented. Farmers started believing that there is no hope. Depeasantisation in agriculture started. Such sentiments weaken the edifice of a democracy. Policymakers should realise that farming is not a hobby but is imperative for the food security of the nation. In the last few years, the awareness level of farmers about the political and economic dimensions of farmers distress has improved. Intelligent farmer movements have evolved as the young generation of educated farmers is also participating in mobilisation of farmers. This can gauged from the fact that farmer protests are not restricted to only demonstrations and blockades but their agenda provides solutions to the problems. There is a tectonic shift in the perception of the farmers.

The harvesting of kharif crops has commenced and farmers are occupied in reaping and post-harvest operations like storage and disposal of crops but they will be back on roads after the harvesting season is over. “We staged march from Haridwar to Delhi to discuss the complete gamut of issues. We were given assurance by the Union Government on our demands but it remains to be seen how many of those would actually be addressed? If we are not satisfied with the response of government we will resort to agitation at a larger scale”, said Rakesh Takait, the national spokesperson of Bhartiya Kisan Union. “It is a crucial year, not only for the political parties, but for the farmers also. There is a lot more awareness among farmers as compared to last elections. Farmers are disgruntled because the Modi government rolled out and publicised a plethora of schemes but the plight of farmers has been going from bad to worse. The so-called farmer-friendly plans like Crop Insurance Scheme and Jan-Dhan Yojna have facilitated the redistribution of resources in the favour of corporate players at the cost of impecunious farmers.”

The harvesting of kharif crops has commenced and farmers are occupied in reaping and post-harvest operations like storage and disposal of crops but they will be back on roads after the harvesting season is over. “We staged march from Haridwar to Delhi to discuss the complete gamut of issues. We were given assurance by the Union Government on our demands but it remains to be seen how many of those would actually be addressed? If we are not satisfied with the response of government we will resort to agitation at a larger scale”, said Rakesh Takait, the national spokesperson of Bhartiya Kisan Union. “It is a crucial year, not only for the political parties, but for the farmers also. There is a lot more awareness among farmers as compared to last elections. Farmers are disgruntled because the Modi government rolled out and publicised a plethora of schemes but the plight of farmers has been going from bad to worse. The so-called farmer-friendly plans like Crop Insurance Scheme and Jan-Dhan Yojna have facilitated the redistribution of resources in the favour of corporate players at the cost of impecunious farmers.”

Takait said that the farmers now want implementation. Governments make promises and defer the implementation. He said that farmers want to get rid of debt. Increasing the credit target for agriculture has caused more stress to the farmers as their repaying capacity has not been increasing. Remunerative price crop is more viable solution to the problem of deteriorating condition of farmers. “There are 18 ministries handling the agriculture sector. A nodal agency should be appointed to take care of diverse issues related to farming and post-harvest needs of farmers. The new schemes rolled out with much fanfare like Crop Insurance Scheme and e-NAM have not benefitted the farmers. Barriers to market the produce are there as before and insurance scheme needs to be revised if the welfare of the farmers is actually on the agenda of government.”

After the show of strength of farmers at national level, BKU would continue its stir at district and village level. The huge arrears from the sugar mills towards the sugarcane growers need to be resolved. Takait said that the farmers buy everything in cash and when their payments are withheld the cycle of income generation gets disrupted. Such anomalies are one of the reasons for the flourishing non-institutional credit market in India which exploits the farmers with exorbitant rates of interest.

According to the Agriculture Census 2015-16, close to 67 per cent of the farmers in India are marginal farmers and have average land holding of less than 2.5 acre (one hectare). In contrast, only one per cent of the farmers own large landholdings, having a size of 10 hectares and above. The matter of serious concern is that the percentage of area that was actually operated under the large holding was recorded to be 10.59 percent; which is 10 times more than the land ownership of large farmers. At the same time, it was 22.50 percent for the marginal farmers against the land ownership of 67 per cent, indicating a huge gap of land allocations for cultivation between small and big producers.

The average size of landholding was estimated to be 1.15 hectare, again indicative of a skewed distribution of land. According to the Economic Survey 2017-18, net irrigated area to net sown area in the country is about 48 percent but studies conducted by the international organisations have put the reliably irrigated area in the range of 40 per cent. The eight-member inter-ministerial committee under the chairmanship of Ashok Dalwai, constituted by the Modi Government for doubling the farmers income by 2022, estimated the average annual income of a farmer in India at 77,976 .

A close scrutiny of this figure depicts the hardships of the farmers and non-viability of farming as a profession for the small and marginal landholders. This highlights the purchasing power of a farmer in our country, who may not be able to provide two-square meals to his family with the given annual consumption budget. A study conducted by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development that was published in State Focus Paper 2018-19 (Punjab) on the time required to double the farmers income explains that doubling farmers income by 2020 may be a wishful thinking. According to the study, the time to double the farmers’ income at compound annual growth rate of 5.2 per cent at the annual income of 77,124 is estimated to be 13.56 years.

Thus, it is evident that the rhetoric of doubling of farmers income in next three to four years a pipedream. Farmers have not been able to recover even the input costs.

The interpretation of remedies for farmers’ miseries cannot be done in terms of simply raising the nominal income. It has to be correlated to the inflation rate as well. Merely increasing the income cannot save farmers if there is a proportionate increase in the cost of inputs.

Spiralling diesel Prices

Hike in the fuel prices adds burden on farmers directly and indirectly. Direct impact is in the form of increase in the diesel price. Indirect impact is felt in the garb of revised prices of all inputs. The hike in diesel price from an average 48 per litre to 80 per litre has increased the cost of cultivation. The cost of fuel price is built into all the goods and a service purchased and leads to inflation in all the sectors. As a consequence of frequent price revisions of fuel price during the regime of Modi government, the cost of cultivation has increased by 1500-2500 per hectare depending upon the crop, for the farmers who practice mechanised farming. This has squeezed the margins of the farmers because the remuneration of the crops has not increased proportionately.

Indebtedness

Why has the indebtedness being rising despite rapid expansion of banking and higher credit allocation year-on-year? Prof Satish Verma, an RBI Chair Professor at Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development, Chandigarh, said that indebtedness in not the key reason for the predicament of the farmers, though it has been the triggering factor in most of the cases. Indeed, indebtedness is the manifestation of a number of factors through which the thread of suicides is commonly believed to run. It is mainly the agricultural distress rooted in crop failure, depressing prices of agricultural products, rising cost of production, lack of irrigation facilities, monsoon failures, floods, pest attacks, spurious seeds and pesticides and policy paralysis, that is the igniting factor leading to farmers’ suicides. Diverting loans for non-productive purposes has also been widely quoted as the factor that ultimately causes the farmer to commit suicide in the event of his failure to repay the loaned amount. Raising loans from the moneylenders and commission agents has always been stressful that, in some cases, has also induced suicides.

Farmers have diverse credit needs and all of these cannot be met by the banking sector. Farmers require funds for meeting domestic as well as other non-productive expenditures. Banks extend credit for productive purposes only. Crop loans, which are eligible for interest subvention of three per cent subject to fulfilment of the terms and conditions, account for the major share in agriculture credit. Since the banks do not have control over the end use of these funds, the possibility of their diversion for non-productive purposes is quite high. Ultimately the farmer finds himself in a position where he is unable to return the amount and takes recourse in suicide. In some cases, the farmers borrow from the commission agent/moneylender to pay off the debts that he owes to the banks. In this case, ultimately he finds himself caught in debt trap and commits suicide. The banks have Debt-Swap Scheme to free the farmers from loans due to the moneylenders, but progress of the scheme is not satisfactory.

Punjab, for example, is an agriculturally prosperous state with almost 100 per cent public procurement of food-grains (wheat and paddy). Farmers in the state witnessed huge prosperity during and in the period immediately followed by the green revolution. This prosperity was well aided by the government policy of providing agricultural inputs at highly subsidised rates and keeping the prices of food-grains at higher levels. This provided them huge margins that the farmers used for up-scaling their living standards. In the subsequent period — starting particularly from the era of liberalisation of 1991 — the liberal import of food-grains depressed their prices in the local markets. Also, the government followed a policy of keeping the food prices low to ensure food security in the country. The cost of production also rose at a rate much higher than the output. Indeed, the terms of trade between agriculture and non-agriculture sector which was favourable before 1991 turned unfavourable for agriculture sector in the subsequent period.

Thus, the farmers’ margins in the post liberalisation period continuously declined while their expenditures did not fall correspondingly as they had become accustomed to a particular standard of living following the green revolution.

Moreover, the cost of essential services such as education and health skyrocketed in the post liberalisation period. Hence, maintaining living standards became out of reach of the paying capacity of the farmers which put him in a state of quagmire and distress.

The number of farmers’ organisations operating in the country is quite large. These have affiliations with the political parties that have vested interests that are opposed to each other.

Therefore, the farmers need to unite themselves under a common banner that will serve only the farmers’ movements rather than sub-serve the interests of the political parties.

Climate change and agri income

The rising temperatures and changing climate is an area of concern for agriculture economists as it may affect the productivity in agriculture and undermine the farmers’ income. The Economic survey of 2017-18 had pointed out that the climate change will affect the productivity and farmers’ income. No matter how much we invest in inputs and soil fertility, the vagaries of weather (excess or scanty rain) can negate all the investments.

According to A Nambi, Director, (Climate Resilience Practice), World Resources Institute (WRI India), agriculture in India is facing sundry problems and climate change is one of the factors affecting agriculture. He said that tropical weather is very complex and difficult to understand. Right information at the right time is critical to help the farmers. Climate information can help to save the crops from sudden weather change.

“Climate change is a global phenomenon and the entire world is struggling to find solutions as it affects the basic human need of food. Our country has worked in this direction and our preparation in terms of planning for agriculture and climate change is at par with other countries of the world. But we lag when comes to implementation. The State Action Plans have been framed but the ground level implementation is tardy. Some states are pro-active but many have not achieved the desired results. There is a tepid response from states on the climate related initiatives. In Australia, climate information is sought right from sowing to packaging of agriculture produce. A rigorous implementation of policy framework can help tremendously to reduce crop loss due to weather vagaries. Another problem with India is its vast and diverse geography. India has 121 agro-climatic zones and there are challenges in implementation. We need to devise institutional thinking. Climate risk management should be administered. Access to weather information is critical but the requisite inputs should be made available in a short period. The availability of inputs at the right time is the most effective means to minimise the loss due to adverse climate. Farmers face either glut of scarcity in the input market that restricts the benefits of risk management. Our job does not end with releasing forecasts. We need to collect regular feedback from the farmers on the recent impact of the climate and difficulties faced by the them as a result of adverse climate. We need to analyse current situation and prepare suggestions for the next 10-15 years. Another factor that affects the condition of farmers is political decision making. The distress of farmers can be remedied to a great extent if right policies are implemented at the right time. For instance, farmers should move away from wheat and paddy in Punjab and Haryana. But the assured price and procurement infrastructure, which is not available for other crops has impeded the diversification towards other crops. The farmers in some pockets of Himachal Pradesh have been forced to diversify from apple to other crops as the rising temperatures are not conducive for apple farming. Thus, climate change has forced them to shift to other crops. Proactive transformation adaptation is a solution that can be adopted in Asia and Africa,” said Nambi.

Paddy straw management has become a burning issue as the pollution emanating from burning of paddy straw pollutes a vast stretch in north India up to New Delhi. It has health and economic implications. The road, rail and air-connectivity get disrupted due to smog. But the burning of paddy affects farmers and their families the most as they inhale the smoke with highest content of harmful gases. The states of Punjab and Haryana spearheaded the setting up of thermal power plants run on biomass by inviting private power players under renewable energy mission. But it could not work out as the transportation cost of biomass makes the revenue model of such projects non-viable. The government has roped in research institutes and universities to explore solution to this problem. Due to mechanisation, the harvesting span has been compressed to three weeks and managing 20 metric tonne (only in Punjab) is a huge task and available solutions are not adequate.

Farmers are struggling with disposal of stubble as they have to prepare their fields for the next crop. The state governments have been propagating the recycling of paddy straw through in-situ management. This includes incorporation of paddy residue in the soil or its retention on the surface.

Crop Insurance

The crop insurance scheme, rolled out with fanfare during the Modi government, has not benefitted the farmers. Farmers allege that this has created holes in their pockets as the banks deduct the premium of insurance cover from their loan account without their consultation. For illiterate farmers, seeking the compensation of crop cover is an arduous task. It has been reported that the insurance companies have earned a business of 24,000 crore, but the compensation of only 8000 crore was distributed in a year. Farmers have been demanding to revise the criteria of insurance cover but of no avail.

The farmers’ suicides in India are the manifestation of agrarian crisis in the country. According to reports, farmers’ suicides account for 11.2 per cent of all suicides in the country. The phenomenon of farmers suicides came to the light during 1990s. As per official government figures, between 1995 to 2004, approximately 3 lakh farmers committed suicides. The actual number could be higher, according to the agriculturists). The farmers are not equipped with any other skill-set to earn their livelihood. Under immense pressure from banks and moneylenders, they decide to end their lives.

The manifestation of growing resentment and massive congregations of farmers with roadmap for sustainable solutions is indicative of tough going for the political parties. Farmers are vociferous about their demands and uniting for their cause. They understand that their demands are incorporated in the election manifesto of political parties but forgotten after attaining the power. “Last general elections, we went with the wave but this time we have many questions. We may not have money and muscle power but we have ballot power and this time we will use it prudently,” said a farmer from Uttar Pradesh. There is a writing on wall. Time will tell who could read it.

letters@tehelka.com