The Assam government’s decision to shut down state-run madrasas and Sanskrit schools in the state has met with vehement criticism from all quarters. The religious organisations and leaders from across the spectrum have expressed displeasure at the decision of the Education Minister of the state, Hemanta Biswa Sarma, to do away with state funding of religious institutions.

The Assam government’s decision to shut down state-run madrasas and Sanskrit schools in the state has met with vehement criticism from all quarters. The religious organisations and leaders from across the spectrum have expressed displeasure at the decision of the Education Minister of the state, Hemanta Biswa Sarma, to do away with state funding of religious institutions.

The decision for which a formal notification is to be announced in November 2020 is being justified with the assertion that the state exchequer should not be financing religious institutions. The BJP government proposes to extend and support modern education across every nook and corner of Assam. It claims that the funds will be diverted to strengthening the educational institutions, and some of the teachers from the madrasas and Sanskrit schools to be transferred to other schools under the state education department.

The move has come under severe backlash from the Muslim organisation across the country and prominent leaders from the community. The Lok Sabha MP representing Dhubri Assam and AIUDF chief Badruddin Ajmal lashed out at the state government saying the Muslims will no longer vote for BJP in case they went ahead with the decision. He lamented that the future of students enrolled in these institutions could be jeopardised with the decision. Ajmal also said his party would re-open the madrasas after coming to power in the next year’s Assembly elections

The central education board of Jamaat-e-Islami Hind also expressed condemnation of the decision by the Assam government announcing to shut down all the government-run madrassas. The chairman of the board, Nusrat Ali, said that on one hand, the government talks about universalisation of education and connecting the socially and educationally backward classes with the education, and on the other hand announce such decisions. He said the Jamaat’s education board would pursue all democratic and legal means for maintaining the financial support of madrasas. Many Hindu priests also condemned the government move, saying the dying Sanskrit language will only suffer more if the schools were not supported.

Speaking to the media, Sarma the government had announced the decision in the Assembly earlier. “Our policy is clear, there should be no religious education with government’s funding,” he added. The announcement was made while some legislators were demanding provincialisation of madrasas in the state. The decision had been in the pipeline since February this year when the government first indicated it was contemplating closing down madrasas.

According to political analysts, the decision of the BJP-led government is politically motivated and a move to satisfy the aspirations of their supporters. Speaking to Tehelka, a leading minority rights advocate from Assam termed the move as being ‘political symbolism.’ Requesting anonymity, the activist said, “They are doing this to show that the BJP government stands against Muslims. Assam is 8 months away from the elections and the Chief Minister says Assam is still under attack from Mughals. There are no pretensions from BJP that it is communal and prejudiced against a community,” he added.

Constitutional validity

So what does the constitution say? The articles 29 and 30 of the Indian constitution lay down certain rights of minorities, which may not be taken away by the state. Article 29 states that any community in India shall have the right to conserve their languages, script and cultures. Clause 2 of the same article provides the right to citizens to not be denied admission into state maintained and state-aided institutions only on the grounds of religion, race, caste, or language.

Article 30 of the constitution talks about rights of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions. The article, under Clause 2, prohibits the government from ‘discriminating against any educational institution’ on the grounds that it is managed by a minority community, while granting aid to educational institutions.

“The Education Minister says Madrassas are imparting religious instruction, and it is prohibited under Article 28 of the constitution. But the fact remains that the syllabus of madrasa doesn’t come under the definition of religious instruction but ‘a study and research of Arabic language.’ There is no violation of Article 28. A government which doesn’t respect the spirit of the constitution, its preamble, basic structure, is invoking constitutional provision — that’s the mother of all irony,” the Guwahati-based advocate said.

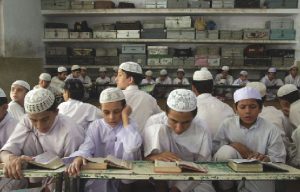

The state of Assam is currently supporting around 614 recognised madrasas, out of which 57 are for girls, 554 are co-educational, 3 are boys and 17 are running under Urdu medium, according to the website of the state madrasa board. There are also more than 2000 madrasas, run through donations from the public and private organisations. Likewise, the state has around 1,000 recognised Sanskrit tols, out of which only about a hundred are supported by the government.

The state of Assam is currently supporting around 614 recognised madrasas, out of which 57 are for girls, 554 are co-educational, 3 are boys and 17 are running under Urdu medium, according to the website of the state madrasa board. There are also more than 2000 madrasas, run through donations from the public and private organisations. Likewise, the state has around 1,000 recognised Sanskrit tols, out of which only about a hundred are supported by the government.

State funding since 1800s

The madrasa education system in Assam goes back to the 1780s, when the British East India Company first helped establish it. In 1915, through the efforts of Nasar Mohammad Waheed, the renowned educationist and administrator, madrasa education was further improvised through new schemes. According to the website of the state madrasa education board, these institutions serve the most under-privileged children in remote areas and don’t just impart religious education.

“The idea that it (madrasas) imparts religious and theology based education to a particular religion is not true. In fact, the madrasa education in West Assam is fulfilling the constitutional commitment by providing access to free education up to secondary level for the most deprived people most of whom are first generation learners live in rural areas where avenues and opportunities are markedly limited. Most of the madrassas are situated in the remote rural areas of the state and they were founded with the initiative of community donations,” it says.

The local Muslim population is conspicuously disappointed with the decision, with many saying their rights are being taken away gradually. They allege that the BJP government’s decision was planned, and for years the government had not allowed the recruitment of teachers for the madrasas in which the number of students was exorbitantly high.

While prominent Muslim leaders and activists in the state are expected to put a united front agains the implementation of the decision, however, it seems unlikely that their efforts will result in any success. Tehelka spoke to lawyers who said they were going to fight the decision in the court and had full faith in the judiciary. The decision is expected to materialise in the month of November, and the government may start covering madrasas into schools, and transfer teachers from also to these schools.

The decision has attracted little criticism from the national parties in New Delhi, which is why it is expected to be an easy sailing for the BJP-led government. The only few voices that were raised on social media were from the Muslims themselves, with little or no comments from the opposition parties in the country.

letters@tehelka.com