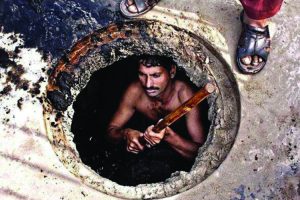

Manu V, 25, died of asphyxiation on March 2 while cleaning a sewage pit in a school in Begur, Bengaluru. The owner of the school has been arrested. But it won’t bring back Manu or people like him, who lose their lives to the stinking legacy of suffocation and stigma. Every year, hundreds of manual scavengers die asphyxiated by poisonous gases across the country despite legislations being in place that prohibit involvement of human beings in such practices.

Manu V, 25, died of asphyxiation on March 2 while cleaning a sewage pit in a school in Begur, Bengaluru. The owner of the school has been arrested. But it won’t bring back Manu or people like him, who lose their lives to the stinking legacy of suffocation and stigma. Every year, hundreds of manual scavengers die asphyxiated by poisonous gases across the country despite legislations being in place that prohibit involvement of human beings in such practices.

Since 1993, when the Parliament had passed a law outlawing the employment and use of manual scavengers, scant little has been done to secure their most essential rights. The unwillingness to enforce the ban and the lack of alternatives provided by the government to ensure that humans are not engaged in cleaning sewers make this illegal and inhumane practice prosper.

Many times, concerned authorities are indirectly involved in it. Municipal corporations and local bodies very often outsource the sewer cleaning tasks to private contractors, who do not maintain proper rolls of workers. In case after case of sanitation workers being asphyxiated to death while working toxic sludge pools in different parts of the country, these contractors simply deny any association with the deceased.

Amid all this, the introduction of a fleet of 200 machine-equipped trucks to deal with scavenging by the Delhi government is a step in the right direction. It may not bring the scourge of manual scavenging in the capital to an immediate end. But the technology deployment for cleaning purposes may put pressure on other states to take measures to curb this practice.

During a survey last year by the Centre, the governments of Haryana, Bihar and Telangana did not report even a single manual scavenger. But the task force conducting the survey — which comprised members from the ministries of social justice, rural development, drinking water and sanitation, and housing and urban affairs and the National Safai Karamchari Finance and Development Corporation — found that there were 1,221 manual scavengers in

Bihar. Haryana had 846 such workers and 288 people in Telangana were engaged in this dehumanising practice.

The latest official statistics suggests that more than 45,000 people have been identified by various states as manual scavengers. Of them, over 37 per cent are yet to receive the one-time cash assistance they are entitled to under the government’s rehabilitation scheme that was launched in June 2018.

In the 2019-20 Interim Budget, the Modi government allotted just 9 crore for the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis. In 2018-19, only 5.92 crore was set aside for the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis and in 2017-18, the figure was 4.5 crore. As per the socio-economic and caste census of 2011, a total of 182,505 households are still dependent on manual scavenging across the country.

The governments need to take action to ensure that the dehumanising practice of manual scavenging stops at the earliest. Washing the feet of safai karamcharis is fine but only concrete measures and their proper implementation will lift the manual scavengers out of their woes.

letters@tehelka.com