More than six years after the abrogation of Article 370 and the downgrading of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories, a familiar but politically fraught demand has resurfaced with renewed intensity: the creation of a separate state for Jammu. What distinguishes the current moment from earlier phases of the debate is not just the volume of voices from Jammu’s civil society, but the sharp and ideologically divergent reactions it has triggered across the Kashmir Valley, cutting across party lines and unsettling long-held political positions.

The resurgence of the demand also unfolds against a conspicuous backdrop: the Centre’s continued silence on restoring statehood to Jammu and Kashmir, a promise repeatedly articulated since August 2019 but yet to be honoured.

Civil society push in Jammu

The immediate trigger for the latest round of debate was a meeting of civil society representatives in Jammu city earlier this month. Over 70 participants—comprising intellectuals, academics, business leaders and social activists—came together to articulate what they described as “persistent political, economic, and developmental challenges” faced by the Jammu province since 1947.

The resolution adopted at the meeting alleged “sustained discrimination” against Jammu, accusing Kashmir-based political leadership of an “overtly anti-Jammu orientation” and chronic neglect in political representation, resource allocation, infrastructure development and employment generation. Participants argued that despite Jammu’s strategic importance, demographic diversity and contribution to the region’s economy and security, it has remained marginalised in governance and policy-making.

The resolution asserted that the demand for a separate Jammu state was “neither reactionary nor driven by parochial considerations,” but was instead a “survival need” rooted in the pursuit of equitable governance and political dignity. It committed to peaceful, constitutional mobilisation and announced plans for similar consultations across Jammu’s districts.

While calls for Jammu statehood are not new, their articulation by civil society rather than mainstream political parties gave the demand fresh traction, and prompted swift responses from across the political spectrum.

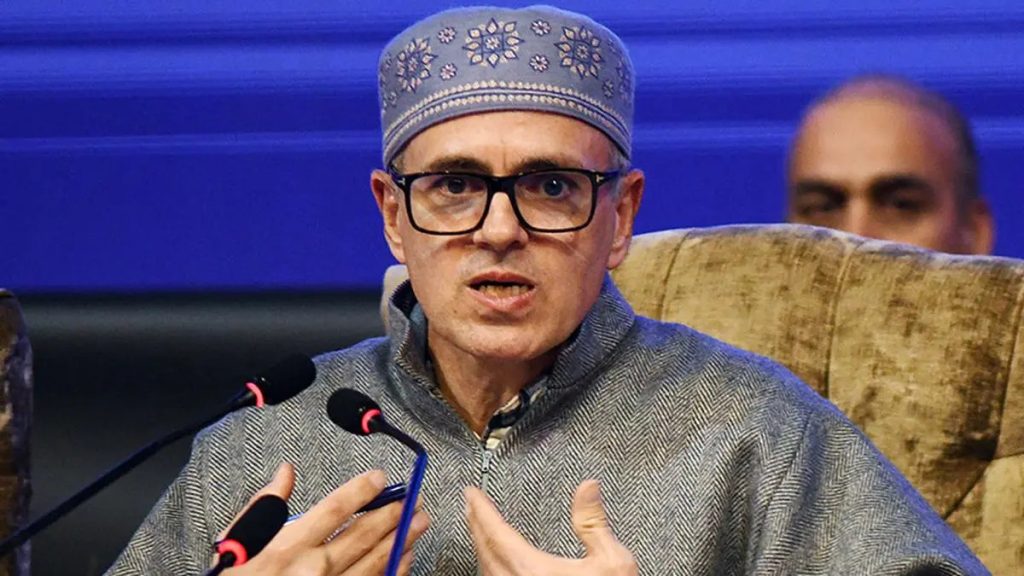

Omar Abdullah draws a red line

Chief Minister Omar Abdullah was unequivocal in rejecting the idea of bifurcation, framing it as both divisive and harmful to Jammu’s long-term interests. Speaking at the National Conference’s two-day Block Presidents’ Convention in Jammu, Abdullah said, “As long as the plough-bearing flag of the National Conference continues to fly across Jammu and Kashmir, no power on earth will dare attempt to divide the region on regional or religious lines.”

Positioning his government as pro-Jammu, Abdullah cited initiatives such as increased ration quotas, free bus rides for women, enhanced pensions, free land for landslide victims and the restoration of the historic Darbar Move. He accused the BJP of hollow symbolism and selective outrage, remarking that “those who stopped the Darbar Move or celebrated the closure of a medical college cannot claim to be Jammu’s well-wishers.”

Taking a direct swipe at Leader of Opposition Sunil Sharma, Abdullah dismissed bifurcation rhetoric as personal ambition. “If he wants to be Chief Minister, why only Jammu and not J&K? If ambition drives him so much, let him contest Jammu municipal elections,” he said, adding that such politics would not find support beyond parts of Jammu city.

Abdullah also warned that regional polarisation would damage Jammu’s interests rather than advance them, reiterating that the National Conference would not allow “narrow, divisive politics” to shape the region’s future.

A Valley counter-narrative emerges

Even as Omar Abdullah rejected bifurcation, a strikingly different tone emerged from sections of the Kashmir Valley’s political leadership—some of whom went further than Jammu’s civil society in questioning the very basis of a unified Jammu and Kashmir.

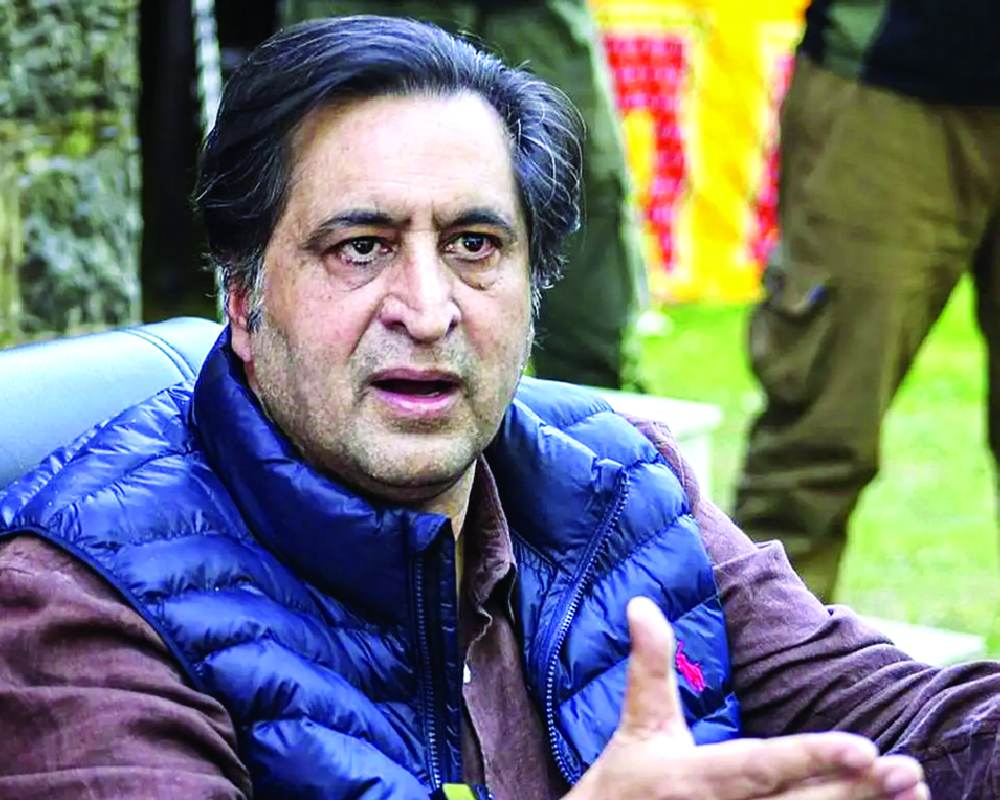

People’s Conference president Sajad Lone became the first mainstream Kashmiri politician to openly call for what he described as an “amicable divorce” between the two regions. In a statement, Lone said, “Maybe time has come for an amicable divorce. It is not only about developmental matters. Jammu has become the proverbial stick to beat the Kashmiri with.”

He argued that resentment had grown deep on both sides, adding, “I think the people of Kashmir too can’t take it anymore… I am sure the desire for divorce is much, much higher in Kashmir than it ever was. Need leadership to call a spade a spade.”

Lone accused Jammu-based leadership of “selective courage,” claiming they remained silent when the Centre revoked Article 370, diverted businesses and halted the Darbar Move, but showed aggression only against Kashmir. He also rejected demands that every central institution proposed for Kashmir be relocated to Jammu, saying, “They have an IIM. What is wrong if a Law University comes to Kashmir?”

Former Srinagar mayor Junaid Azim Mattu echoed similar sentiments, asserting that separation would actually benefit Kashmir. “If it happens, it would be a favour for Kashmir rather than a loss,” Mattu said, arguing that the idea of a united Jammu and Kashmir had “no historical, cultural or linguistic basis.”

Mattu traced the political arrangement to the Treaty of Amritsar, calling it unjust, and alleged that Kashmir had paid a far heavier price in terms of lives lost, while Jammu received concessions and sympathy. He accused successive governments of favouring Jammu in reservation policies and access to opportunities, describing shrinking prospects for Kashmiri youth as “collective political punishment.”

Institutional flashpoints and polarisation

The renewed polarisation has been fuelled by a series of controversies around institutions—most notably protests against Muslim students’ admission to a new medical college in Katra and opposition to the proposed National Law University in Budgam. These flashpoints have sharpened the “Jammu versus Kashmir” narrative and reinforced perceptions of regional competition rather than shared governance.

Chief Minister Abdullah has countered claims of discrimination by pointing to the allocation of premier institutions. “Jammu got both an IIT and an IIM, where was the talk of equality then?” he asked, noting that calls for regional balance emerged selectively.

The Centre’s silence looms large

Underlying all these debates is a deeper constitutional uncertainty. Since August 2019, when the Centre revoked Article 370 and downgraded Jammu and Kashmir into a Union Territory, New Delhi has repeatedly promised restoration of statehood “at an appropriate time.” That timeline, however, remains undefined.

Political observers argue that this prolonged silence has created a vacuum now being filled by competing regional narratives. Without clarity on statehood restoration, demands for alternative political arrangements—be it separate Jammu statehood or administrative separation—gain traction.

Ironically, while Jammu’s civil society frames statehood as a remedy for perceived marginalisation, Kashmiri leaders like Lone and Mattu view separation as liberation from what they see as constant vilification and political instrumentalisation.

A debate without a roadmap

Despite the sharp rhetoric, there is little indication that the Centre is inclined to redraw internal boundaries in Jammu and Kashmir. Historically, New Delhi has viewed bifurcation proposals as strategically sensitive, fearing they could weaken India’s position on Kashmir.

Yet, the absence of a clear roadmap for restoring statehood has left regional anxieties to fester. Omar Abdullah’s firm rejection of bifurcation underlines a political reality: while there is consensus across parties on the demand for full statehood, there is no shared vision on what governance should look like if that demand continues to be deferred.

For now, the debate over a separate Jammu state reflects not just regional grievances, but a deeper crisis of trust—between regions, political actors, and the Centre. Until the question of statehood restoration is addressed decisively, Jammu and Kashmir’s politics appears destined to remain caught between unresolved past promises and an uncertain constitutional future.