2021 has turned out to be a year in which everything changed. The ferocity of the Covid-19 second wave has overwhelmed India and the real economy indicators moderated through April-May 2021 indicate a demand shock — loss of mobility, discretionary spending, unemployment and inventory accumulation. However, massive vaccination drive, performance of the agriculture sector and IT give hope to the country, writes BHARAT HITESHI

The impact of the new infections appears to be U-shaped. Each shoulder of the U represents sectors that are weathering the storm — agriculture at one end and IT on the other. On the slopes of the U are organized and automated manufacturing on one side and on the other, services that can be delivered remotely and do not require producers and consumers to move. These activities continue to function under pandemic protocols. In the well of the U are the most vulnerable — blue collar groups who have to risk exposure for a living and for rest of society to survive; doctors and healthcare workers; law and order; and municipal personnel; individuals eking out daily livelihood; small businesses, organized and unorganized — and they will warrant priority in policy interventions.

It is in this direction that the Reserve Bank, re-armed and re-loaded, has stepped out. The RBI on May 21 announced that it will transfer a surplus of 99,122 crore to the Government of India for the financial year 2020-21. This dividend is for the nine-month period from July 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021. The dividend announced is 73.5% higher than the 57,128 crore transferred for financial year 2020. The Government of India had budgeted 53,511 crore worth of earnings by way of total dividend from RBI. This is almost double the amount budgeted for 2022. The increased payout could help the Government of India meet its budgetary obligations and in the revival of the economy.

The dividend comes as a breather because the demand shock is likely to put pressure on indirect tax targets. The increased dividend is also likely to help the Government meet the unexpected increase in expenditure on health care precipitated by the second wave of the pandemic.

RBI WARNING

It is worth mentioning that the RBI in its monthly bulletin released on May 17 had observed that “the biggest toll” of the ongoing second wave of Covid-19 is “demand shock”. It listed other negatives — “loss of mobility, discretionary spending and employment, besides inventory accumulation”.

RISING UNEMPLOYMENT

The unemployment rate remained in double digit in the week ended May 23, latest data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) showed, highlighting the fact that the localised lockdowns have started hurting the economy and jobs. The all India weekly unemployment rate inched up to 14.7% in the week to May 23, marginally higher than the 14.5% in the previous week. In urban India, the weekly unemployment rate was at 17.4%, rising sharply from 14.7% on May 16 while in rural areas it was at 13.5%, lower than the previous week’s 14.3%, according to CMIE data.

Mahesh Vyas, managing director and CEO of CMIE said in a post on his website, “The double-digit unemployment rate seen in recent times indicates that even these restrictions are taking a toll on the economy.” He said the urban unemployment rate has been on the rise since early April 2021. On April 1, the 30-day moving average urban unemployment rate was 7.2%. By May 1, it had reached 9.6% and then by May 23 it was 12.7%. Vyas said the rise of unemployment in rural India is a more recent phenomenon.

DECLINE IN EARNINGS

Now a new report, ‘State of Working India 2021: One Year of Covid-19’, recently released by Azim Premji University, says that the pandemic has led to a severe decline in earnings for the majority of workers resulting in a sudden increase in poverty. The report documents the impact of one year of Covid-19 in India, on jobs, incomes, inequality, and poverty. The report shows that the pandemic has further increased informality and led to a severe decline in earnings for the majority of workers resulting in a sudden increase in poverty. Women and younger workers have been disproportionately affected. Households have coped by reducing food intake, borrowing, and selling assets. Government relief has helped avoid the most severe forms of distress, but the reach of support measures is incomplete, leaving out some of the most vulnerable workers and households.

The main findings of the report are that about 100 million jobs had been lost during the nationwide April-May 2020 lockdown. Most were back at work by June 2020, but even by the end of 2020, about 15 million workers remained out of work. Incomes also remained depressed. Average monthly household income per capita in October 2020 4,979 was still below its level in January 2020 5,989. Job losses were higher for states with a higher average Covid case load. Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi, contributed disproportionately to job losses.

During the lockdown and in the months after, 61% of working men remained employed and 7% lost employment and did not return to work. For women, only 19% remained employed and 47% suffered a permanent job loss during the lockdown, not returning to work even by the end of 2020. Younger workers were much more impacted, experiencing higher job losses, of a more permanent nature. 33% of workers in the 15-24 years age group failed to recover employment even by December 2020. This number was only 6% in the 25-44 years group.

Though incomes fell across the board, the pandemic has taken a far heavier toll on poorer households. In April and May, the poorest 20% of households lost their entire incomes. In contrast the richer households suffered losses of less than a quarter of their pre-pandemic incomes. Over the entire eight-month period (March to October), an average household in the bottom 10% lost 15,700, or just over two months’ income.

Households coped by cutting back on food intake, selling assets, and borrowing informally from friends, relatives, and moneylenders. An alarming 90 per cent of respondents in the AzimPremji University Covid Livelihoods Phone Survey reported that households had suffered a reduction in food intake as a result of the lockdown. Even more worryingly, 20 per cent reported that food intake had not improved even six months after the lockdown.

It suggests that bold measures will be required to emerge stronger from the crisis but so far India’s fiscal response to Covid-19 has been conservative. The states, who are at the forefront of the pandemic response in terms of containment as well as welfare, are severely strained in their finances. There are thus compelling reasons for the Union government to undertake additional spending now. It has proposed extending free rations under the PDS beyond June, at least till the end of 2021, cash transfer of 5,000 for three months to as many vulnerable households as can be reached with the existing digital infrastructure, including but not limited to Jan Dhan accounts, expansion of MGNREGA entitlement to 150 days and revising programme wages upwards to state minimum wages. Expanding the programme budget to at least 1.75 lakh crores. It has also suggested a pilot urban employment programme in the worst hit districts, possibly focused on women workers.

VACCINATION DRIVE

On January 3, 2021 India formally approved the emergency use of two vaccines and on January 16, it launched the world’s biggest vaccination drives, with plans to inoculate about 300 million people on a priority list this year. Global support has poured in, with over 40 governments committing to help India with medical essentials. The World Trade Organisation’s Director-General NgoziOkonjo-Iweala tweeted: “India unselfishly exported over 40 per cent of her vaccines. Timely for India to get this support”. The US has decided to divert vaccine-related raw materials to India for production of vaccines. Gilead Sciences and Merck, two large US has pharmaceutical companies, took steps to expand access to their drugs in India through the voluntary licensing route, while committing support to Indian companies manufacturing Remdesivir as well as contributing 450,000 vials up-front12. Russia began exporting the Sputnik V vaccine to India from May 1, 2021. Oxygen concentrators, liquid oxygen, cryogenic oxygen tanks, oxygen cylinders, mobile oxygen production plants and ventilators have been reaching through air and sea from a host of other countries — Singapore; the UK; France; Germany; the UAE; Ireland; Australia; Saudi Arabia; Hong Kong; and Thailand. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has sanctioned US$1.5 billion to support India’s pandemic response.

WHAT GIVES HOPE?

There are, however, glimmers of hope amidst the gloom. At the end of the first half of May, the test positivity rate in the ‘maximum city’ Mumbai, among the worst-hit in the second wave, dipped to 7.9 per cent now from 26.6 per cent in early April. Daily new cases in the city have declined from a recent peak of 10,000 on April 7 to around 2400 now. Discharges are higher than daily detections and as a result, the active caseload has fallen from a peak of 90,000 on April 12 to about 40,000 as at present. India’s second wave hit Mumbai (and Maharashtra) first. Therest of India may hope that its trajectory is a sign ofthings to come.

Meanwhile, gold wrapped up a phenomenal year, which saw bullion prices scaling an all-time high in August, with gains of 25.1 per cent, following up the 18.3 per cent ascent in the previous year. Safe haven demand and unprecedented monetary accommodation made bullion a top-performing asset in 2020. Gold prices have corrected in 2021 so far with sell-offs due to waning safe haven demand as also due to the dollar gaining strength. In recent months, gold imports have risen sharply, April marking the seventh consecutive month of expansion in both value and volume terms on top of record gold imports in March. According to the Gems and Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC), improvement in demand conditions in major export destinations, pent up domestic demand for weddings postponed earlier along with the festive season, have pushed up demand for gold and jewellery. Improved business and consumer sentiments, reduction in customs duty, ebbing of gold prices from record peaks in August 2020 and the appreciation of Indian Rupee vis-à-vis US Dollar in 2020-21 has also attracted retail investment in gold. Basking in gold’s glory, silver had a good year too. Base metals, which had seen a sharp dip in the initial months of the year, recovered strongly in 2021.

Cross-country comparison indicates that India is on the move, ahead of other economies. The six largest states — Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Gujarat and West Bengal — recorded 87 per cent of normal footfalls in public places, the best levels so far in the pandemic (Mint tracker). Aggregate demand conditions have either consolidated recent gains or vaulted up on strengthening pace. Electricity consumption expanded at 5.0 per cent year on year, maintaining its growth for the fourth successive month. Northern and central states such as Madhya Pradesh (15 per cent), Rajasthan (12 per cent), Bihar (14 per cent), Punjab (12 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (10 per cent) experienced a surge in power demand due to increased heating load. Mercury levels plunged to multi-year lows as an unusually intense winter took hold with La Nina cooling the waters of the Pacific and a cold wave gripped most of upper India, interspersed with sporadic unseasonal showers in these states.Consumer confidence is regaining its groove. Purchasing behaviour is expected to reveal a preference online and offline towards health and well-being products, ahead of a bigger shift to value added goods and essentials via digital and omni-channel sales. Alliances between e-commerce players and kirana stores are expected to expand to increase service delivery to meet rising demand. Upbeat consumer sentiment is also expressing itself in housing. There are signs of the housing sector turning around, with a sharp uptick in 2021 in sales of residential units — almost double the level of the preceding quarter — supported by favourable interest rates, still restrained housing prices, steep discounts by developers to clear inventory, and reduction in stamp duty by a few states.

AGRICULTURE UNSCATHED

Agriculture remains unscathed by the pandemic. Though the farmers protesting against the three farm laws and government has given no heed to the protests, the agriculture remains the sunrise sector giving a glimmer of home in such times for economic revival. How has the second wave impacted the economy? In a pandemic, such assessments tend to get blurred by disproportionate base effects and hence, measuring momentum can shine some light into the haze, as discussed in Section III. High frequency indicators for April and May 2021 are scanty in view of data lags, but they suggest that the biggest toll of the second wave is in terms of a demand shock — loss of mobility, discretionary spending and employment, besides inventory accumulation.

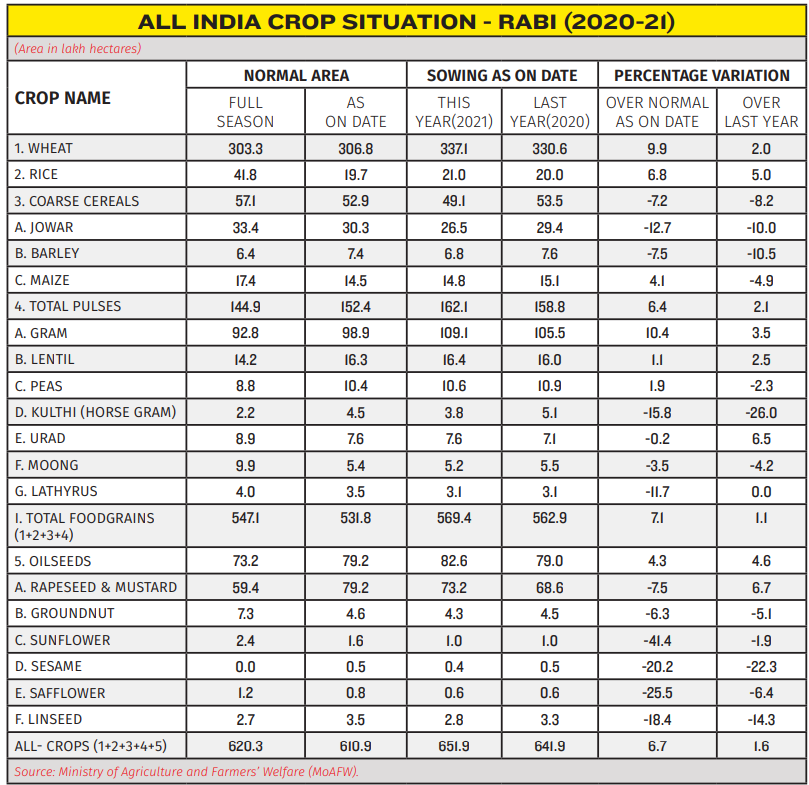

Agriculture remains robust. Sowing of major crops has exceeded the normal acreage levels. Rabi sowing covered an area of 651.9 lakh hectare in 2021, 1.6 per cent higher than in the preceding year, and surpassing the full season normal acreage. The reservoir levels stood at 68 per cent of full capacity as against the decennial average of 56 per cent; this is an important force multiplier for the rabi season. Wheat — the primary rabi staple — has recorded an increase in sowing acreage (2.0 per cent), mainly due to higher sowing in major producer states, notably Haryana (1.2 per cent) and Madhya Pradesh (12.7 per cent). Pulses and oilseeds have also registered an impressive turnaround in acreage. With record kharif production, procurement of kharif rice at 51.3 million tonnes was 26.2 per cent higher than a year ago, taking the cereals (rice and wheat) buffer stock to 3.7 times the norm.

Aggregate demand conditions have been impacted, albeit not on the scale of the first wave. Goods and services tax (GST) collections in April at 1.41 lakh crore were the highest since the introduction of GST. E-way bills — an indicator of domestic trade — recorded double digit contraction at 17.5 per cent month-on-month in April 2021, with intrastate and inter-state e-way bills declining by (-)16.5 per cent and (-)19 per cent, respectively.

Preliminary data on petrol and diesel sales point to a decline in fuel demand in April, attributable to mobility restrictions. Diesel sales contracted by 1.7 per cent m-o-m, while petrol sales declined by 6.3 per cent in April 2021. Electricity generation in April stagnated month-on-month but over the pre-pandemic base of April 2019, it increased by 8.1 per cent, indicating a limited hit of the second wave on industrial activity. On a year-on-year (y-o-y) basis, electricity generation expanded by 39.7 per cent.

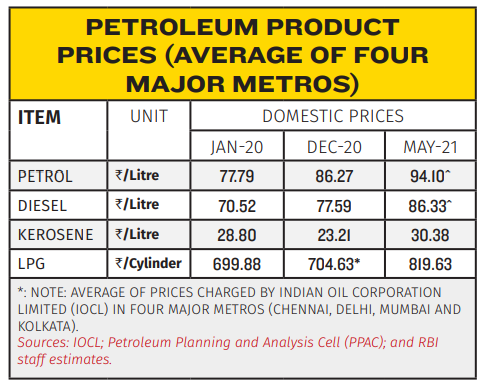

With international crude prices on an upward trajectory since mid-April 2021, domestic pump prices also increased with a lag from early May onwards. Between May 3, 2021 to May 12, 2021 petrol and diesel pump prices (average of prices in four major metros) increased by 1.53 per litre and 1.85 per litre to 94.10 per litre and 86.33 per litre, respectively (As on May 25, 2021) . A litre of petrol in Mumbai now comes for 99.71 and diesel is priced at 91.57 per litre. At this level, pump prices are scaling new historic highs. International commodity prices are also registering sharp increases, cutting across agricultural, industrial raw-materials and energy segments. This is leading to a worsening of domestic cost conditions.