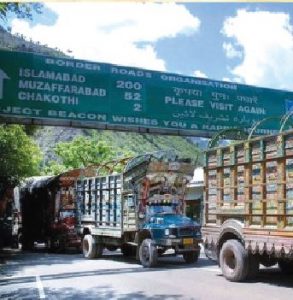

Trade between India and Pakistan has been officially banned. But a trade route between India and Pakistan, worth hundreds of crores, is flourishing nevertheless. People from both countries continue their cross-border trips and with them comes and goes the business of cotton saris, dhotis, cosmetics, betel leaves, cashmere wool and much more.

Trade between India and Pakistan has been officially banned. But a trade route between India and Pakistan, worth hundreds of crores, is flourishing nevertheless. People from both countries continue their cross-border trips and with them comes and goes the business of cotton saris, dhotis, cosmetics, betel leaves, cashmere wool and much more.

The crowded bylanes of Meena Bazaar and parts of Karol Bagh in Delhi are the exchange centres — for items ranging from synthetic cloth, cotton to cosmetics are traded for money. The Samjhauta Express, which runs from Lahore to Delhi, and the Lahore-Delhi bus serve to bridge the gap between the two nations. Pakistanis from Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad bring to India almonds, dried grapes and synthetic cloth. Indians carry their cotton saris, dhotis, cashmere shawls and cosmetics to trade in Pakistan.

The trade is clandestine, no two ways about it. No longer is it restricted to family members living across the border exchanging goods: people now travel regularly across the border strictly for business.

“There are people who travel from both countries solely for business reasons. Special guesthouses have also been set up to collect the goods and then transfer them to Pakistan and sell them in India,” says Afzalur Rahman Khan, general secretary of the Moulana Azad (Meena Bazaar) Shopkeepers’ Association.

Pakistanis from Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad bring to India almonds, dried grapes and synthetic cloth. Indians carry their cotton saris, dhotis, cashmere shawls and cosmetics to trade in Pakistan

Many hotels have sprung up to accommodate the peripatetic residents of Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad during their stay in India. The Jama Masjid and Paharganj areas are teeming with seedy hotels and shops that function as currency exchange centres between the Indian and the Pakistani rupee. “We have a lot of customers who come from Pakistan to sell their goods,” says Ali Muhammad, manager of a Chandni Chowk hotel. “They are generally shopkeepers or traders from Lahore and Karachi and they bring along dupattas, almonds and so on.”

The difficulty lies in transporting the goods. People travelling to Pakistan by train carry extra bags and bedding stuffed with cotton saris, dhotis and cosmetics. “It is much easier to carry goods in a train than in a bus,” says a trader. The more savvy business people, however, ferry their goods by air.

But the process is hardly as straightforward as it sounds. Many palms have to be greased in customs and excise to wheedle a dash across the border. “Everybody in official circles knows about this business,” says Shamim Khan, a shopkeeper who has travelled to Lahore to sell cotton saris. “But they prefer to maintain a discreet silence. The business ought to be legalised, because the amount of money being earned could only benefit the country.”

Making contacts across the border is usually a matter of word of mouth. When word gets around that someone is going to Pakistan, a trader who is a friend of a friend might ask the traveller to lug along some goods and deliver them to a trading counterpart in Pakistan. As visas on both sides of the border are difficult to procure, those who have managed a trip to Pakistan are loaded with all manner of goods.

“Those going to Lahore carry the goods. The trade has been going on for a long time and people know whom to contact. But the government should relax the visa system so that more people can travel to Pakistan,” says Afzalur Rahman.

General Pervez Musharraf’s visit to Delhi might end up doing a lot more than bring the Kashmir crisis that much closer to resolution: it might make the border more legally porous. Till then, however, goods and money will continue to roll in through the wide open back door.

letters@tehelka.com