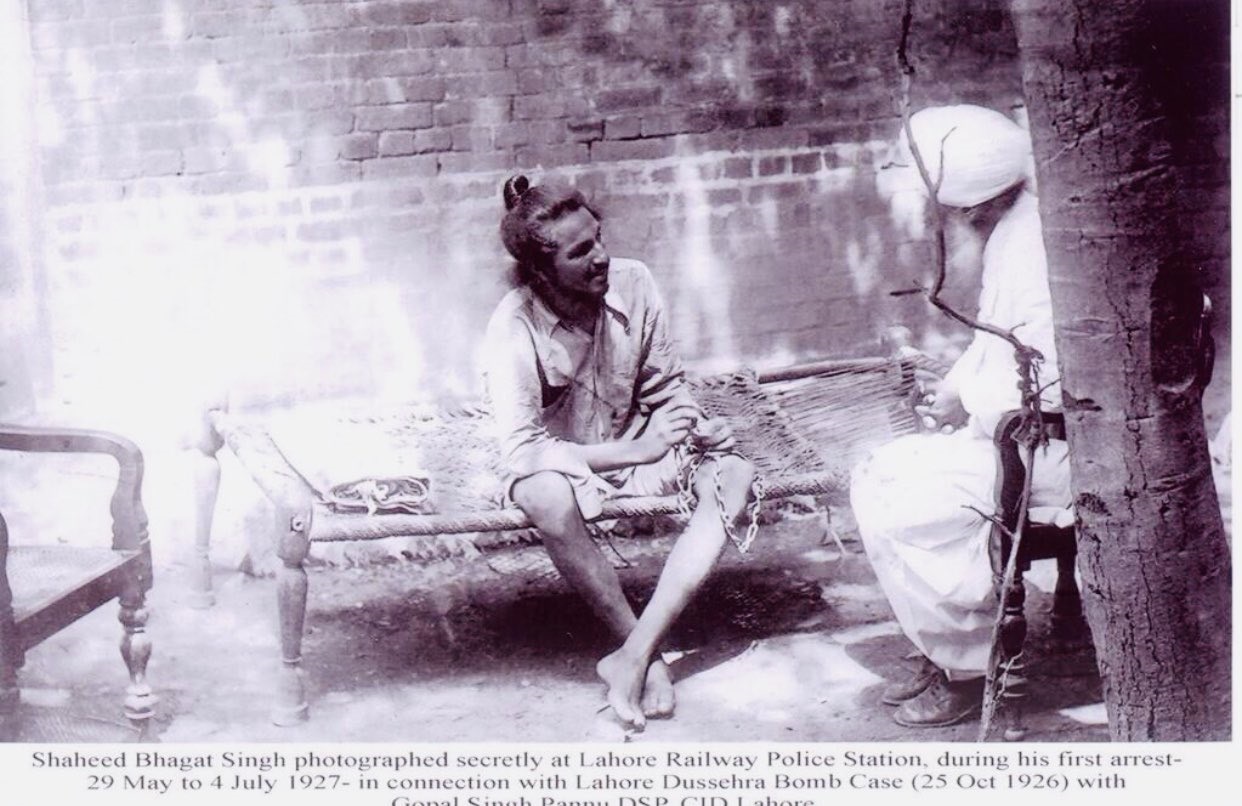

Shaheed Bhagat Singh, whose 115th birth anniversary fell on September 28 last, was not only a great patriot and revolutionary socialist but also a Marxist thinker and ideologue of high calibre. Quite early in his life, he had become a voracious reader. He was only 23 when he was hanged in 1931. One wonders how he had packed so much in his short and eventful life, writes Raj Kanwar

Fortuitously, literature on the Soviet Union and the revolutionary movements in Italy, Ireland and Russia, and the writings of Marx, Engels and Lenin, were easily available in Lahore at the Dwarkadas Library that had been founded by Lala Lajpat Rai. From an early age, Bhagat Singh was one of the major users of the Library. He greedily read books on revolutions. No wonder then that Bhagat Singh and his comrades ‘looked upon the Socialist Russia as an ideal’, writes Editor DN Gupta in his book “Select Speeches and Writings of Bhagat Singh”.

A voracious reader

That was not all; his reading interest extended to novels by the iconic writers of those times like Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo, Oscar Wilde and the like who wrote on widely varied themes. Dickens was an English writer and social critic who lived in the 19th century (1812-1870) England. The general theme of his books largely revolved around ‘Humour’ and ‘Pathos’ as in ‘Oliver Twist’. Oscar Wilde on the other hand is best remembered for his epigrams and plays in the second half of the 19th-century-England. His most talked about play was “The Picture of Dorian Gray”, in which he tells an English Lady, “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.” Another favourite author of Bhagat Singh was Victor Hugo — the French poet playwright, novelist, statesman and a human rights activist. His famous novels were ‘Les Misérables’ and ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’. All these authors wrote on subjects as different as chalk and cheese.

In an article on Bhagat Singh in the Times of India, historian Prof. MM Juneja (formerly of Chhaju Ram Memorial Jat PG College, Hisar) had written: “Bhagat Singh studied a lot till his arrest on 8 April 1929. He continued reading albeit with greater vengeance even in jail. One of his co-prisoners Shiv Verma had then said, ‘Though we all had a passion for reading, Bhagat Singh was in a class by himself. His love for books was legendary. As per some estimates, he had read nearly 50 books while in the School, and about 200 during his College days till his arrest in 1921, and approximately 300 books during his incarceration of 716 days (April 8, 1929 to Mar 23, 1931).’

His love for books endured till the last minute

Throwing some light on Bhagat Singh’s thirst for books, Raja Ram Shastri, a well-known librarian of Dwarka Das Library, Lahore (now shifted to Chandigarh), had once told Shiv Verma, ‘Bhagat Singh literally used to devour books. He would read books, make notes, discuss with his friends and critically examine his own understanding in the light of new knowledge, rectifying the mistakes that came to be discovered.’

His love for books endured till his last breath, literally! Pran Mehta, Bhagat Singh’s lawyer was allowed to meet him on March 23, 1931, just a few hours before the hanging. Bhagat Singh was then pacing up and down in the condemned cell like a lion in a cage. He welcomed Mehta with a broad smile and asked him if he had brought him Vladimir Lenin’s book, ‘State and Revolution’. As soon as he was handed the book, Bhagat Singh began reading it as if he was conscious that he did not have much time left. Soon after Mehta’s departure, Bhagat Singh was told that the time for hanging had been advanced by 11 hours. By then, he had finished only a few pages of the Book.

In the same context, a close associate of Bhagat Singh, Manmathnath Gupta wrote about those last moments, “When called upon to mount the scaffold, Bhagat Singh was reading a book by Lenin or on Lenin, he continued his reading and said, ‘Wait a while. A revolutionary is talking to another revolutionary.’ There was something in his voice which made the executioners pause. Bhagat Singh continued to read. After a few moments, he flung the book towards the ceiling and said, “Let us go.”

Bhagat Singh’s patriotism was inbred

Not many among generations X and Z would perhaps know about Bhagat Singh and his heroic battle against the erstwhile colonial British rulers! In some ways, he was a genius and a born-leader. In fact, his patriotism was inbred. His father Kishan Singh was in Lahore Central Jail, and uncle Ajit Singh in Mandalay jail when Bhagat Singh was born. He had grown up listening to the stories of the exploits of both his father and the uncle. The Ghadar movement had also left a deep imprint on his impressionable mind. What had impressed him the most about the Ghadarites was their international outlook that separated religion from politics. “He was particularly inspired by the courage, self-sacrificing spirit and patriotism of another revolutionary Kartar Singh Sarabha who was hanged in the first Lahore Conspiracy Case when he was barely 19. He adopted Sarabha as a role model and carried his photograph in his pocket.”

The massacre in Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar on April 13, 1919 too had left a deep scar on his young mind so much so that he drove all the way from Lahore to Amritsar just to kiss the ground that had been sanctified by the martyrs’ blood.

In the first decade of 20th century, Bhagat Singh’s family lived in a non-descript village Banga (Tehsil Jaranwala) in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad in Pakistan). His father, Kishan Singh owned a fair amount of agricultural land. Bhagat Singh’s academic career had begun moderately in the district primary school where he studied up to class V. He completed the rest of his schooling from Lahore’s iconic DAV High School (it was the alma mater of this writer too).

From the DAV School, Bhagat Singh moved to the National School in 1921 that had been founded by the trio of Lala Lajpat Rai, Bhai Parmanand and Sufi Amba Parshad (Bhatnagar). He was then just 14. It was there that he had also met his future comrades – Sukh Dev, Bhagwati Charan Vohra and Yashpal. At the National School, Prof. Jai Chandra Vidyalankar had become his mentor of sorts, and narrated the exploits of the revolutionaries in the erstwhile United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). All those revolutionary stories had so deeply inspired the young teenager that he then and there decided to dedicate his life to the cause of liberating Bharat Mata from the clutches of the British Imperialists.

A dynamic writer too

Apart from being a voracious reader, Bhagat Singh was also a dynamic writer. “Within just a period of seven years (1923-30), he wrote on various subjects like God, mysticism and religion, language, art, literature, culture, biographies of past and contemporary revolutionaries and other political leaders, and most important of all on party organization and revolution,” writes DN Gupta in his book. Bhagat Singh had constantly fought against ‘obstructionist, sectarian and communal ideologies’. No wonder then that the most outstanding and path-breaking pamphlet on religion and existence of God “Why I am an atheist”, and the reasons for believing so was written by him during the evening of his life.

If Bhagat Singh was to appear on today’s political horizon, he would feel aghast at the increasing emphasis that the current ruling dispensation in India placed on the supremacy of religion to the exclusion of everything else. He had once told his comrades that “communalism was a great enemy of Indian society and Indian nationalism. Religion should at best be considered as the ‘private concern’ of an individual.”

Sadly there was not much love lost between the Congress and Bhagat Singh. And he would be an anathema to the current ruling BJP dispensation. Thankfully, at least AAP (Aam Admi Party) swears by Bhagat Singh, and has

raised him to an iconic stature in the Punjab where it is the ruling party.

(Raj Kanwar is a 92-year old Dehra Dun-based veteran journalist, writer and author. His latest books are Dateline Dehra Dun and its sequel.)

tehelkaletters@gmail.com