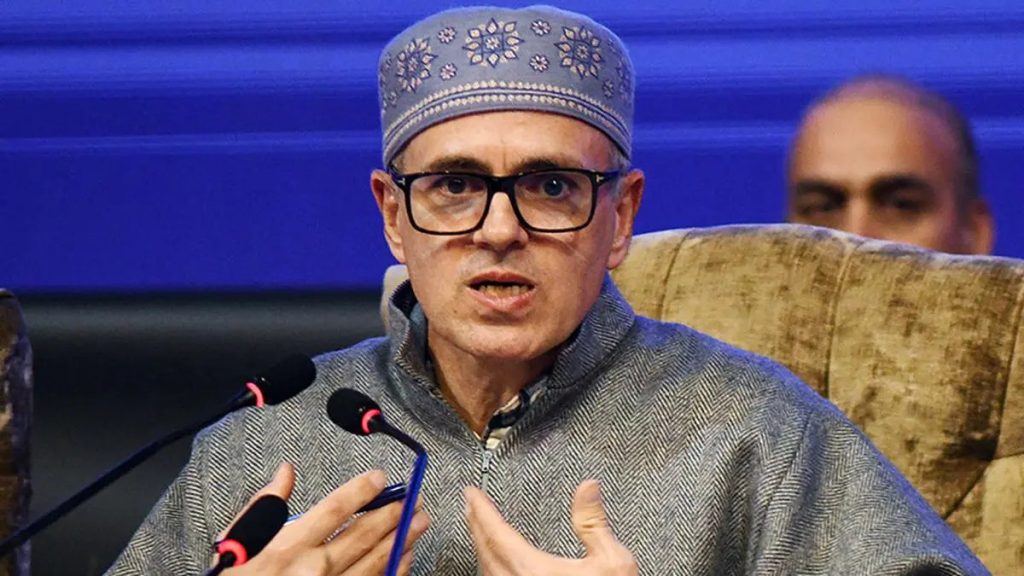

When Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah recently remarked, “If I don’t have snow, I can’t sell Gulmarg,” he was not merely making a tourism pitch. He was articulating a deeper, unsettling reality: Kashmir’s economy, ecology, and identity are increasingly hostage to a rapidly changing climate.

Speaking at the annual convention of the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India (ATOAI) in Srinagar, Abdullah openly acknowledged what many in the Valley have been witnessing for years — receding glaciers, shrinking snowfall, and growing uncertainty around winter tourism. His suggestion that Kashmir may need to turn to artificial snow-making technologies to sustain skiing in Gulmarg marked a significant shift in public discourse, signalling that climate change is no longer a distant concern but a present-day crisis demanding adaptation.

This winter has offered stark evidence. Kashmir is experiencing an unusually dry and snowless season, marked by bright blue skies and sunlit days more reminiscent of early spring than deep winter. While the warmth may appear benign on the surface, its consequences threaten to cascade through multiple sectors — tourism, agriculture, hydropower, and water security.

A Winter Without Snow

November and December, which usually witness the snowfall, have passed largely dry. December recorded an 86 percent rainfall deficit. Most plains across the Valley have not received snow, while the upper reaches have seen significantly below-average snowfall.

More troubling is the absence of any immediate forecast suggesting a sustained return of snow, particularly in the plains. All eyes are now on Chilai Kalan, the harshest 40-day phase of winter beginning on December 21 when Kashmir typically receives its heaviest snowfall. Its first day saw some modest snowfall on upper reaches, so there is hope that more may follow including in the plains. A dry Chilai Kalan is rare, though not unprecedented; similar conditions were last recorded in 2015 and 2018. However, the growing frequency of such winters has heightened alarm among scientists.

Data shows that nine of the past 28 winters have been largely snowless, three of them in the last decade alone. While historical records over the past 127 years do indicate occasional dry winters, scientists say the long-term trend over the last five to six decades is unmistakable: snowfall volumes have declined sharply. Where plains once received nearly a metre of snow, they now see only a few inches — a shift largely attributed to global warming.

Glaciers in Retreat

The implications extend far beyond tourism. Snowfall during January and February plays a critical role in glacier nourishment, which in turn sustains Kashmir’s rivers through the summer months. Reduced snowfall means weaker glacier recharge, leading to diminished river flows during peak agricultural and power-generation periods.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the Kolahai Glacier, Kashmir’s largest and most significant glacier. Situated at an altitude of around 3,600 metres in the upper reaches of Pahalgam, Kolahai feeds the Lidder and Sindh rivers, both major tributaries of the Jhelum. Scientific studies show that Kolahai has shrunk from 13.87 square kilometres in 1976 to just 11.24 square kilometres, retreating at an alarming rate of 0.08 square kilometres annually.

Earth scientist Shakil Ahmad Romshoo has warned that Kolahai alone has lost nearly 30 per cent of its area between 1992 and 2025, with the most severe recession occurring in the last decade. Other glaciers tell an equally grim story. Najwan Akal, once a major glacier in the upper Sindh Valley, has disappeared entirely. Thajwas, Zojila, and Naranag glaciers — which historically persisted until late autumn — have receded dramatically.

The loss of glacier mass poses a direct threat to water availability, especially during the summer months when demand peaks. It also undermines hydropower generation, a crucial component of Jammu and Kashmir’s energy mix.

Tourism on Unstable Ground

Tourism, particularly winter tourism, remains one of Kashmir’s most climate-sensitive sectors. Gulmarg’s global reputation as a skiing destination depends almost entirely on consistent natural snowfall. In recent years, however, snowfall has become increasingly unpredictable — often arriving late, well after the peak holiday season.

Hotels, tour operators, and tourists alike report growing frustration. Visitors arrive expecting snow-covered landscapes, only to encounter bare slopes and brown meadows. In response, authorities and tourism operators have started talking about experimenting with artificial snow, a stopgap solution increasingly common in ski destinations worldwide.

Yet artificial snow is energy-intensive, water-dependent, and environmentally contentious — especially in a region already grappling with water stress. While it may help sustain tourism revenues in the short term, experts warn it cannot replace the ecological role of natural snowfall.

Chief Minister Abdullah has also called for diversification of adventure tourism, promoting activities such as paragliding, hot-air ballooning, and year-round outdoor experiences to reduce dependence on winter snow. But even diversification offers limited insulation if climate volatility continues to intensify.

Agriculture Under Stress

Climate shifts are also unsettling Kashmir’s horticulture sector, particularly apple cultivation, which forms the backbone of the rural economy. Apple trees require a specific number of chilling hours during winter to flower properly in spring. Warmer winters and erratic precipitation are disrupting this cycle.

Basharat Bhat, an orchardist from Budhan village in north Kashmir’s Baramulla district, says unseasonal snow and rain have led to fluctuating yields. “Changing weather patterns affect pollination,” he explains. “Low temperatures or rainfall during the flowering stage reduce fruit set, directly impacting production.”

Such disruptions threaten not only farm incomes but also export volumes and employment across the apple value chain.

A Larger Climate Pattern

Meteorologists note that Kashmir’s weather is influenced by complex interactions between western disturbances, local topography, and global climate systems. However, broader trends are impossible to ignore. Rising global temperatures, deforestation, increased vehicular emissions, and higher energy use for heating are all contributing to long-term warming across the Himalayan region.

The El Niño phenomenon, driven by abnormal warming of surface waters in the Pacific Ocean, has further altered global weather patterns, often resulting in drier winters and reduced precipitation across South Asia. Recent winters in Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh have mirrored this trend, with snowfall weakening or arriving well beyond its usual window.

A Crisis Demanding Choices

The snowless winter unfolding in Kashmir is no longer an anomaly — it is a warning. The Valley stands at a crossroads where climate change threatens to erode economic stability, ecological balance, and cultural rhythms tied to the seasons.

Artificial snow may keep ski slopes operational, but it cannot replenish glaciers, recharge aquifers, or sustain rivers. Long-term solutions will require climate-resilient planning, reduced emissions, forest conservation, water management reforms, and honest recognition that the old climatic certainties no longer apply.

As Omar Abdullah’s blunt remark underscores, Kashmir cannot sell winter without snow. The larger question now confronting the region is whether it can adapt fast enough to survive a future where snow itself can no longer be taken for granted.