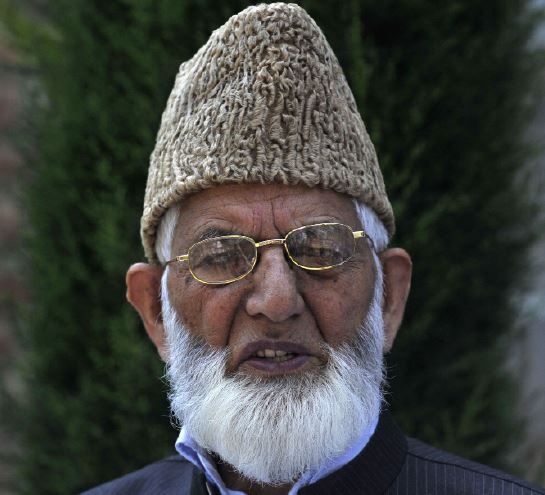

Why symbolism of the dead Geelani would be a bigger problem for New Delhi to deal with than the frail, old leader it had confined to his home over the last decade, explains RIYAZ WANI

On the evening of September 1, as Kashmir went agog with rumours about the passing of the top hardline Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani, the security forces quickly put the region under a lockdown, a drill they had done several times over in anticipation of his death. After the death was confirmed, Geelani’s house at Srinagar’s uptown Hyderpora was quickly sealed. Neither the public nor the media were allowed near the site.

What unfolded thereafter has since triggered a simmering resentment in the Valley: A viral video that emerged from the Geelani’s house shows police allegedly snatching the leader’s body and burying it quietly at a nearby graveyard, without the participation of his sons.

Though police later also released a video showing that it had performed gusl (full ablution) of Geelani before his burial, it only stirred fresh anger in Kashmir. Police also issued a statement later, saying Geelani’s sons had initially agreed to a quick funeral but changed their minds “probably under the pressure from Pakistan” and “started resorting to anti-national activities”.

Soon after the leading separatist leader’s death, Kashmir was once again put under information blockade. Internet – both broadband and mobile net – and phones including the landlines went dead. Broadband and phones were restored two days later and mobile internet came back online five days later.

The government’s rationale for these extraordinary security measures was to prevent Geelani’s death from triggering mass scale protests in Kashmir. Despite this, there were sporadic protests in parts of the Valley. In some areas, the mosque loudspeakers reverberated with slogans.

But due to the extraordinary security bandobast and the sweeping communication blackout the protests didn’t catch on beyond a point.

The silence in Kashmir, however, could be deceptive. Although not reported in the local media or widely so in the national media, Geelani’s death has attracted a lot of attention on social media. Thousands of messages and images and to a lesser extent the videos were posted on Twitter and Facebook, many of them by his detractors in India who accused him of being a hardliner and supporter of militancy and Pakistan

In Pakistan, Geelani’s death drew a lot of notice. After the police burial of Geelani’s body went viral, Pakistan summoned Indian Charge d’ Affaires to the Foreign Office and conveyed a strong demarche on “callous and inhuman” handling of his mortal remains. Pakistan also observed a day of mourning over his demise and flew its flag at half mast.

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), a body of Muslim countries, condemned the Indian government for “denying the right to choose burial rites and site for Geelani, an iconic Kashmiri leader”.

However, the government lockdown ensured that the protests didn’t spread beyond a point. And after a few days, the government was able to restore the communications and the situation, by and large, returned to normal.

Geelani had started his career as a leader of the politico-religious outfit Jamaat-i-Islami. He had contested and won three elections from his North Kashmir constituency of Sopore. And before he became known as the most prominent separatist leader, his name was synonymous with Jamaat-i-Islami, his parent party. In fact, it was more of his personal charisma that was largely responsible for making Jamaat a formidable political force in the Valley before the onset of militancy. In 1987, Assembly elections he was instrumental in cobbling together a coalition of political, religious and social parties called Muslim United Front (MUF) which was tipped to be a favourite to win the polls but for the then widespread rigging that brought National Conference-Congress combine to power.

tehelkaletters@gmail.com